Agriculture in Tunisia is facing critical challenges now with the recent findings on the use of phytosanitary products, which are banned in several countries, including Europe and the United States. This raises concerns about soil health, biodiversity, and food security in the country. Nonetheless, promising alternatives such as agroecology and sustainable agriculture are becoming more prominent, offering a holistic perspective for a sustainable transformation of the Tunisian agricultural sector.

News and leaks regarding the sale of some phytosanitary products in Tunisia that are banned in Europe and the United States are multiplying. Nonetheless, no Tunisian official seems to be alarmed.

In April 2022, the environmental investigative journalism publication "Unearthed," operated by the British NGO, Greenpeace, stated that Tunisia is among the countries that imported chlorpyrifos. Tunisia represents the second-largest market for exports of this product from Belgium. The product was banned in the European Union, the United States, and Canada since 2020 due to its harmful effects on children’s neurological development. Studies indicate that it significantly increases the risk of autism, lowers IQ, and causes attention disorders. It is also harmful for the pollination by bees, which are already in danger of extinction worldwide. In addition, in March 2023, chlorpyrifos was detected on Maltese oranges exported to France. These oranges were immediately withdrawn from the market to ‘protect the citizens.’

Although chlorpyrifos poses threat to our health, it was found in analysis results of on citrus fruits—an analysis requested by the Tunisian Permaculture Association to certify the production of a young sustainable farmer from the city of Menzel Bouzelfa, which is located in an area known for citrus cultivation. This young farmer has been regenerating his soil and applying sustainable agriculture (also known as permaculture) principles for two years—thus the serious alarm. His certified “citizen food” citrus production was the victim of areo-spraying of chlorpyrifos. Consequently, he was unable to protect his produce, and was obliged to market his high-quality citrus through conventional channels, losing months of work that respected the land and living systems. Although it is also banned in Egypt, Palestine, Morocco, Turkey, among others, this insecticide remains on the list of approved products in Tunisia.

Seed: A Sovereignty Matter

Vegetable seeds included in the official list are largely hybrid seeds, purchased by farmers every year and require the use of phytosanitary products. These seeds have proven limitations, as they are not adaptable to the current drought and are not resistant to diseases, yet those kinds are the only ones legally allowed on the seed market. Moreover, their prices continue to rise, pushing farmers into irreparable debt, alongside the anxiety over the availability of seeds, which diminishes more each year. Reconsidering reproducible seeds that adapt to climate change and are resistant to diseases is also a solution strongly supported by civil society and Tunisia’s gene bank. Furthermore, Peasant Seed Systems (SSP) are being revived to enhance community practices and knowledge and to preserve reproducible viable peasant seeds. These systems have existed since agriculture began but have been dethroned by seed marketing companies that have no interest in making room for established agricultural seed systems. These systems place the farmer at the center of the processes of seed multiplication, selection, and distribution, without claiming any intellectual property rights over them. Although these unrecognized systems guarantee sovereignty for the country, they are closely linked to traditional practices and orally transmitted knowledge that are sustainable, non-polluting, and adaptable to drought and climate change.

How to regenerate soil? How to develop and disseminate the principles of permaculture and agroecology in the current regulatory context in Tunisia? How to combat climate change sustainably when agriculture is dependent on climate?

There are several adaptation measures, such as conservation agriculture, integrated pest management, and optimized water management, but their implementation takes more than listing. It is still difficult to convince farmers not to practice tillage to ensure soil coverage and to limit water evaporation, or use organic fertilizer, for example. Such practices go a long way in conserving the few centimeters of rainwater and combating soil erosion and salinization.

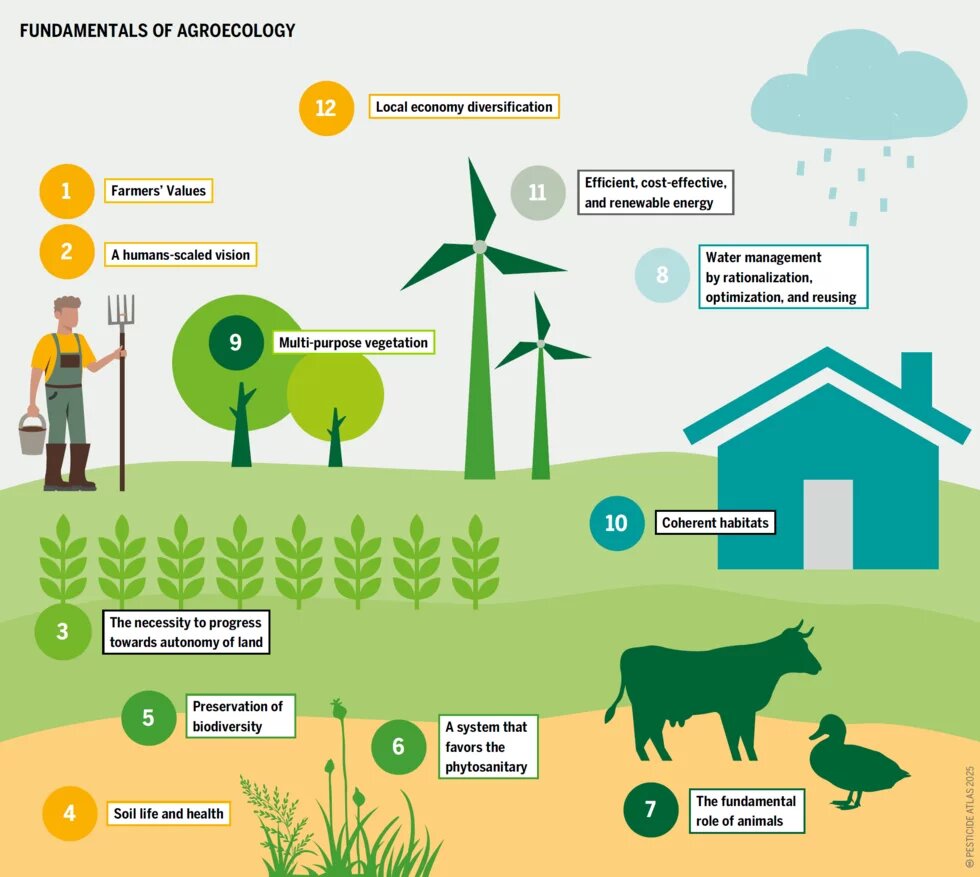

For several years now, researchers at the Institution of Agricultural Research and Higher Education (IRESA) have been considering solutions for Tunisian agriculture that uses as few inputs as possible. The Higher School of Agriculture of Kef (ESAK) and the National Institute of Agricultural Sciences in Tunisia (INAT) have also established master's programs in environmental sciences/agricultural ecology, a subject that is still emerging in Tunisia. Confusion between practices and concepts still exists, even among the educators themselves. The notion of organic agriculture is more empowered because it is linked to a certification that meets a clear set of requirements, while agroecology and sustainable agriculture (permaculture) are more ambiguous and often misused. The concept of sustainable agriculture (permaculture) is not just a mode of production but rather a way of life and a quest for autonomy (food, energy, etc.) which respects the 12 design principles and the 3 ethical principles, aiming to create a resilient ecosystem integrating humans, animals, and plants in a curated space that is not fixed but constantly evolving. Agroecology seeks to design production systems that rely on the functions provided by ecosystems. It focuses more on production techniques while respecting living organisms, working on soil regeneration, and limiting the use of phytosanitary products. Unfortunately, these concepts are not fully mastered by farmers, gardeners, or even within ministries.

Illustration inspired by the work of Terre et Humanisme (Land and Humanity)

What about the Solutions?

Agroecology and permaculture, which aim at creating a “forest-garden” and a resilient ecosystem, are undoubtedly practices that can mitigate the consequences of climate change and can accelerate soil regeneration in the medium and long term, provided a change happens in regulations and pesticide control is imposed, towards protecting consumers’ health. Some Tunisian associations, such as the Tunisian Permaculture Association (ATP) the Tunisian Association of Environmental Agriculture (ATAE), and the Association for the Protection of the Chenini Oasis (ASOC) are guiding young farmers towards these practices, and are achieving promising results, although they have not yet been documented by researchers in Tunisia and are still adequately appreciated.

In the face of the accelerating pace of climate change, water scarcity, and lack of seeds, projects focusing on agroecology have recently multiplied, even if most of them remain tied to practices far from a rounded vision of agriculture. The qualitative shift that the country needs cannot happen without an agricultural revolution that respects living systems, soil health, and the general wellbeing by means of a new vision or production and consumption. The notion of the authentic peasant seed system must also be recognized so that the seed cycles can freely thrive and ensure sovereignty. The farmer who provides the food for the country ought to be at the center of negotiations and discussions. It is also possible to develop a strategic agricultural vision by including orderly training and support for agriculture with high environmental value; one that includes all systems from production to distribution, not overlooking waste recovery.