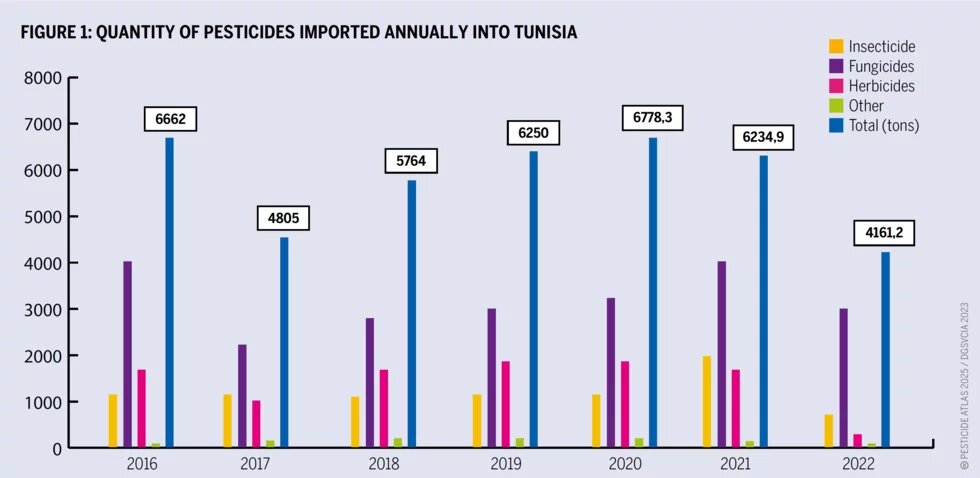

In 2022, Tunisia imported 4,161.2 tonnes of pesticides, reflecting a significant 33 percent decrease from the previous year. This decline is largely due to reduced cultivated areas resulting from drought and water scarcity, alongside a general lack of awareness regarding the severity of the situation and the dangers associated with pesticide use.

Tunisia’s Compliance with International Agreements Regarding Pesticide

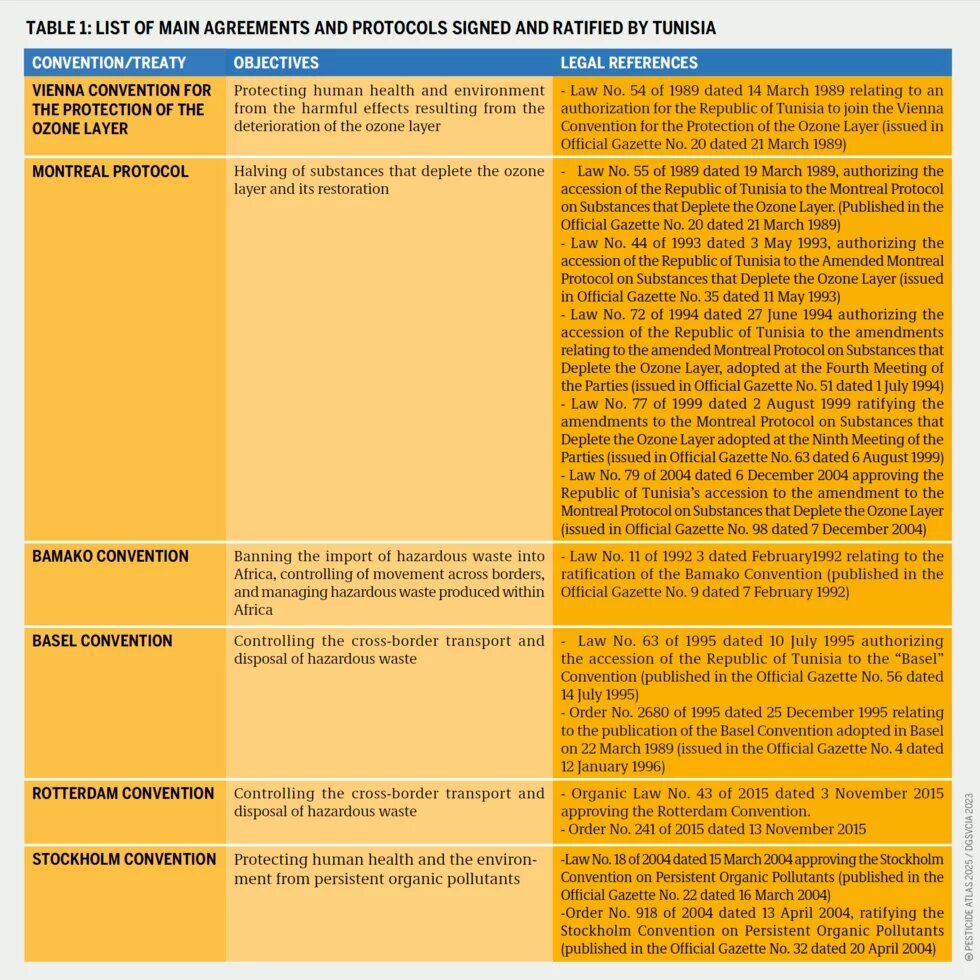

Tunisia has joined multiple international conventions aimed at regulating pesticides and protecting the environment. Table 1 lists the most important ones that are both signed and ratified by Tunisia. Despite Tunisia being a member of the International Labour Organization (ILO), it has yet to ratify the ILO’s Safety and Health in Agriculture Convention (C184).

The evolution of pesticide imports in Tunisia from 2016 to 2022 shows that in 2022, imports totaled 4,161.2 tons, marking a 33 percent decrease compared to the previous year due to the reduction in cultivated areas caused by drought and water scarcity.

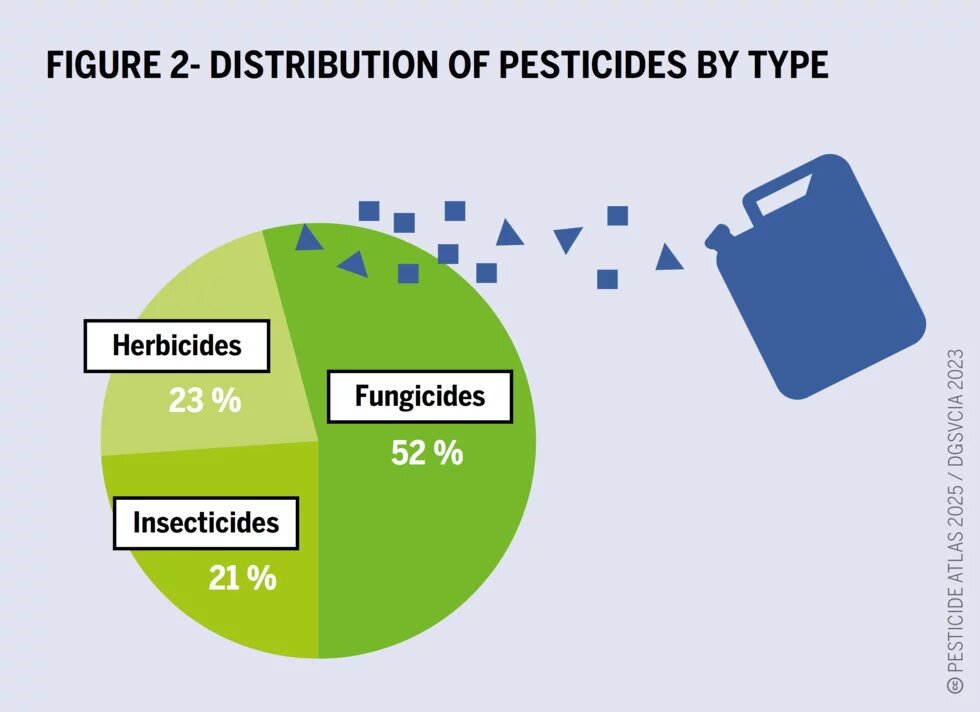

Imported pesticides in Tunisia for the year 2022 were as follows: 52 percent fungicides, 23 percent herbicides and 21 percent insecticides.

National Regulations on Pesticide Use

Since the 1960s, Tunisia has adopted a range of laws aimed at regulating pesticide use. The starting point was with Law No. 61-39 of 7 July 1961; along with its implementing decree No. 61-300 of 28 August 1961. These regulations govern the trade and use of agricultural pesticides and established a process for approval of pesticide products through a technical commission, which was officially formalized in 1977. Additionally, Law No. 92-72 of 3 August 1992, and its implementing decree No. 92-2246 of 28 December 1992, set standards for the manufacturing, importing, formulation, packaging, and marketing of pesticides. Pesticide control is mandated in this decree and is enforced by authorized inspectors who monitor the facilities for the manufacturing, formulation, packaging, and distribution of agricultural pesticides and issue reports accordingly. All agricultural pesticides are automatically inspected upon importation (decree No. 94-1744 of 22 August 1994) by laboratories accredited by the Ministry of Agriculture.

Tunisian legislation also addressed issues related to pesticide control, packaging, repackaging, hygiene, and workers’ health and safety, through Law No. 2002-3469 of 30 December 2002. Other measures have been introduced, such as decree No. 2010-2973 of 15 November 2010, which revises and improves the previous decree No. 92-2246 by specifying the processes for obtaining administrative approval as well as the conditions for importing, packaging, and storing pesticides. In 2011, the government issued decree No. 2011-686 of 4 June 2011 to establish the amount and procedures for collecting contributions related to phytosanitary monitoring, analysis, certification, and temporary licenses for commerce in pesticides. Although Tunisia's regulations largely comply with international standards, there are still delays in implementing provisions that protect vulnerable groups and limit the availability of hazardous pesticides or regulate their use conditions.

Main international conventions on pesticides signed/ratified by Tunisia, with the exception of the International Labour Organization Convention C184 on Safety and Health in Agriculture.

Pesticide Usage and Areas with High Phytosanitary Pressure

There is no policy in place for systematic collection of information and the updating of statistics on pesticide usage by crop, nor their harmful effects on human health or environmental contamination. According to the study conducted by the National Agency for Waste Management (ANGeD) in 2013, the average pesticide usage in Tunisia is estimated to be 0.714 kg/ha.

Banned Pesticides Still in Circulation

Many dangerous pesticides that are banned in Europe are still available on the Tunisian market and are used by local farmers. In 2018, a national report from the Center for Innovation in Agriculture and Industry (IAAA), and which was conducted by CABI, identified 44 extremely hazardous active substances that were approved and shipped to Tunisia, including chlorpyrifos. According to a 2018 study conducted in Sousse Governorate, residues of this pesticide were found in tomatoes at levels as high as 80 percent and 312 percent of the acute reference dose (ARfD) for adults and children respectively. A field survey conducted in 2019, among 27 vineyard farmers over three agricultural seasons (from 2015 to 2017) across six governorates (Ben Arous, Nabeul, Bizerte, Zaghouan, Jendouba, and Béja) revealed that 24 percent of the pesticides used were not approved for grape cultivation or had been withdrawn from the market.

Government Agencies Involved in Pesticide Management and Environmental Protection

Several government agencies are involved in pesticide management in Tunisia, and the following table (Table 2) lists the key players.

However, it is noted that there is no policy aimed at producing and disseminating adequate and accurate educational materials on the use and management of pesticides.

In conclusion, although several laws and decrees have been issued in Tunisia regarding pesticide management and the protection of human health and the environment, there is still a long way to go to align our regulations with constantly evolving international standards.

Regulations Regarding the Protection of Human Health and the Environment

Unfortunately, there are no policies in place to educate users about the importance of protecting health and the environment, or to conduct health-monitoring programs for those who use pesticides in their jobs. The legislation does not contain provisions prohibiting the use of pesticides by children and pregnant or breastfeeding women, nor does it require employers to take the necessary measures to prevent pesticide use by this vulnerable group. However, the legislation does require employers to take the necessary measures to protect workers’ health and the environment. Therefore, they must ensure that all workers, including those in agriculture, are protected by the legal framework.

In this context, a study was conducted by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in 2019 on the effects of pesticides in Tunisia on human health and the environment. The study covered three agricultural regions: Ben Arous, Nabeul, and Monastir, involving 1174 farmers. The study found that only 33 percent of the farmers surveyed ‘used personal protective equipment (PPE)’, while the majority (42 percent) had ‘never worn it’. The remaining farmers surveyed (25 percent) ‘wear only a few pieces of equipment’ that they deemed essential for protecting their health (gloves, shoes, masks). Although they are aware of their importance, various reasons were cited for not using PPE, such as high costs (no subsidy scheme), unavailability on the market, bulkiness, or unsuitability due to high temperatures.

On the other hand, the survey revealed that surveyed farmers showed negligence regarding the health and environmental risks of pesticides. This is evident from practices such as ‘burning empty packaging outdoors’ (63 percent), ‘abandoning waste in nature’ (30 percent), ‘storing pesticide at homes’ (22 percent), and frequently disregarding the recommended dosages and pre-harvest intervals.

The study ultimately highlighted that a large percentage of the farmers surveyed (81 percent) had a low level of education (primary and secondary), and that 91 percent had not received training on best practices for pesticides use. This certainly has serious repercussions on the effectiveness of treatment processes, both for the user’s health, and for environmental pollution.

Several medical studies conducted in Tunisia confirm that exposure to pesticides significantly increases the risk of developing several serious diseases. In a 2020 study, Parkinson's disease was linked to pesticide exposure. Another study published in 2018 found an association between breast cancer and pesticide exposure. Lastly, a 2016 study highlighted the link between pesticides and primary bronchopulmonary cancers (PBPC).

Agroecology vs. Pesticides

The intensification of agricultural production is partly achieved through increased use of pesticides and fertilizers. To preserve our environment and human health, it has become necessary to shift towards healthy methods such as Integrated Pest Management (IPM), which FAO defines as “designing crop protection operations so that their application requires a set of methods that meet environmental, economic and toxicological requirements.” Agroecological crop protection depends on the principles of agroecology to create resilient agroecosystems that can withstand pests and diseases while ensuring the sustainability of cropping systems and environmental preservation. This approach involves adopting various techniques aimed at (i) improving soil fertility, such as crop rotation, using manure as natural fertilizer, intercropping, no-tillage, and applying beneficial microorganisms; (ii) developing biodiversity by enhancing biodiversity within cultivated fields and surrounding areas; (iii) reducing the use of pesticides, thus minimizing reliance on chemical pesticides. Several studies on Integrated Pest Management (IPM) have been conducted in Tunisia. Some of the findings were as follows:

In 2019, a study revealed that controlling the carob worm (Ectomyelois ceratoniae), which attacks a wide range of host plants, was successfully managed using mass trapping techniques that reduced infestation rates in citrus orchards. In 2021, another study found that the carob worm was also controlled in palm orchards. Another study focused on natural predators, such as Trichogramma cacoeciae, used to combat the tomato leaf miner (Tuta absoluta). Lastly, a 2023 study highlighted the use of entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) in conjunction with bacteria to control the wax moth (Galleria mellonella).

A list of the most important Tunisian government institutions and structures concerned with the governance of the pesticide sector

Table 2: List of main government structures involved in pesticide management and environmental protection

| Government Structures | Role | Mandate |

|

DGSVCIA (General Department of Phytosanitary and Agricultural Input Control) |

Certification of pesticides for agricultural use |

- Examination of applications for registration - Verification of the effectiveness of pesticides - Environmental impact assessment - Publication of the list of registered products |

|

- DGSVCIA - ANCSEP (National Agency for Sanitary and Environmental Control of Products) - CRDA (Regional Commissariats for Agricultural Development) |

Application of pesticide legislation |

- Control of pesticide marketing (DGSVCIA) - Coordination with national and international institutions specialised in health control (DGSVCIA) - Participation in the preparation of draft legislation and regulations relating to health control (DGSVCIA) - Proposals and contributions to the drafting of regulations and standards (ANCSEP) - Implementing laws related to animal and plant health (CRDA) |

|

- ANCSEP - DGSVCIA |

Food safety and health problems linked to pesticides |

- Coordination and consolidation of health and environmental control activities for products carried out by the various relevant control structures reporting to the various ministries (ANCSEP) - Analysis of pesticide residues in agricultural products (DGSVCIA) |

|

- ANPE (National Environmental Protection Agency)

- ANCSEP

- ANGeD (National Agency for Waste Management) - CRDA |

Impact on the environment

|

- Drawing up government policy on pollution control and environmental protection and its implementation (ANPE) -Promoting training, education, study and research activities in the field of pollution control and environmental protection (ANPE) - controlling and monitoring the discharge of pollutants and the facilities for treating these pollutants (ANPE) -Pollution prevention, control and elimination (ANCSEP) -Conducting prospective studies on the environment to ensure appropriate conditions for sustainable development (ANCSEP) -Integrated and sustainable waste management (ANGeD) -Improving the institutional, legal and economic and financial management of waste (ANGeD) |

|

-Research institutions affiliated with IRESA (The Agricultural Research and Higher Education Foundation), the most important of which are: - CTAB (Technical Center for Biological Agriculture) - INRAT (National Institute for Agricultural Research in Tunisia) - INAT (National Institute of Agronomic Sciences in Tunisia) |

Agricultural research |

- Encourage and promote alternative solutions to existing pesticides -Developing research programs and experiments - Transfer of technology, training, and coaching

|

|

- AVFA (Agricultural Extension and Training Agency) - CRDA - CTAB - INPFCA (National Institute of Pedagogy and Continuing Agricultural Training)

|

Popularisation, training and support for producers |

- Contribution to the design and implementation of national policies for guidance and vocational training in the agricultural and fisheries sectors (AVFA) - Developing, monitoring and evaluating vocational guidance and training programs (AVFA) - Support for field extension programs developed by the CRDAs (AVFA) - Developing farmers’ skills - Networking between various stakeholders to enhance the transfer of knowledge in research and innovation (AVFA) - Ensuring the research results are adapted to the real conditions on farms (CTAB) - Ensuring guidance and technical support for farmers and training agricultural advisors in the field (CTAB) - Technical support and encouragement (CRDA) - Technical and pedagogical training for mentors (INPFCA) |