Food Sovereignty has been a widely discussed term in the last few years. Nevertheless, the concept of Food Sovereignty exists since the 90s and has since then brought many global organizations together. Some say the term was first used by the farmers’ organization “La Via Campesina”[1]. However, similar organizations and projects have underlined the importance of agroecological farming[2] in order to achieve sovereignty over how and which food we consume, which had existed before the coining of this specific term.[3]Hbs intern Sören Lembke talked to Ms. Lina Isma’il, a food sovereignty activist and Community Programs Officer at Dalia Association, in order to get more insights on the work of food sovereignty activists in Palestine, the challenges and opportunities, and developments in recent years.

What does Food Sovereignty mean to you?

For me, Food Sovereignty means a step towards liberation. To be free to produce our own food, in the way we consider suitable to us while bearing in mind to take care of the land and rebuild our connection with it. It is also a prerequisite for achieving self-sufficiency and reinforcing steadfastness on the land. Moreover, and specifically in the Palestinian context, Food Sovereignty in an emancipatory approach that seeks to break away from all forms of control, among which is the political and economic control.

You just mentioned your “own food” and I have come across the term “culturally suitable food”. Can you explain what you think of this?

The term of “Food Sovereignty”, as defined in the Declaration of the Nyéléni Conference, is “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.” Food production should be derived from our agricultural heritage, related to our own heirloom seeds and our own methods of production. When we talk about our own methods, we mean traditional agricultural methods, not the ones that rely on the use of chemicals, but rather on the inherited knowledge of our environment and land, that is based on a mindset of care and regeneration as opposed to extractivism. It also entails developing practices through experimentation and observations of climatic conditions that are relevant to our seasons and crop varieties. It stands for preserving our culture and identity, what we can plant and farm in our own land, using and reproducing our heirloom seeds that are domestic to the area.

"Food Sovereignty is the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems... Food production should be derived from our agricultural heritage, related to our own heirloom seeds and our own methods of production.”

Often times a distinction between food sovereignty and food security is made. What is the difference between the two terms and why was there a need for the concept of food sovereignty?

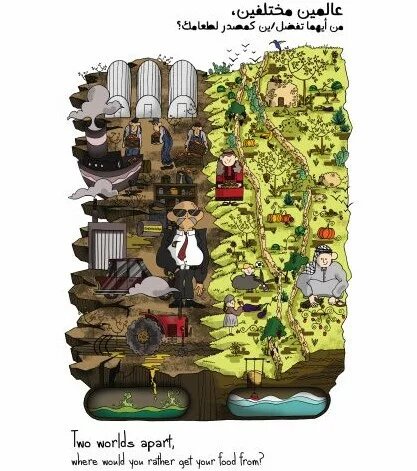

Food security has various definitions, but all focus on the ability to access and purchase food. In its original definition, it means that people have access to affordable and nutritious food, which entails having a purchasing power to buy food from a food supplier, like a supermarket for example, and the availability of this food in the market. This definition does not focus on the process of producing food; where it originates, under which circumstances and which methods are used to produce and sell it. It does not tackle all those issues and only looks into the accessibility to food in general. In contrast to that, food sovereignty focuses on the rights of people to define their own food methods and places food producers at the core. As for the circumstances of production, it highlights social and economic justice as well. It emphasizes the right of farmers to produce food that is culturally and environmentally suitable for them in their own context, to have sovereignty over their own land, the power to decide how to plant, and when to harvest.

In farming methods that do not adopt agroecology and food sovereignty, such as chemical farming and big agribusinesses, farmers rely on external inputs such as chemical fertilizers and pesticides. These inputs put them in debt in addition to the health and environmental risks caused by chemically produced food. Another restricting external input can be the need to import certain seeds, especially genetically modified seeds that are often not reproducible, meaning that the final plant would either not yield seeds or yield ones with inferior quality. Those genetically modified seeds represent a constant economic burden for farmers, in addition to controlling what they should plant based on the availability of those seeds in the market. Such control would not be possible when returning to heirloom seeds that are reproducible.

Food sovereignty is centered on locally available and natural resources and inputs, so the food producer is not chained or bound by big monopolizing companies that aim to have farmers rely on purchasing their seeds and complementary chemical products. Agroecology is at the heart of food sovereignty. Its philosophy and practice promotes a harmonious way of dealing with the land, not overusing vital resources like water nor relying on external inputs. It adopts the variation in food production and rejects monocropping[2]. In this sense, it preserves the land and protects it from harmful diseases. It also protects farmers from the financial risks of price fluctuation as conventional farmers (or farmers adopting industrial agricultural systems) can face big financial crises when one of the few vegetables that they are producing by monocropping loses its price. In agroecology, numerous varieties of crops are cultivated, so a farmer’s income is protected by other crops if one loses its value. Thus, food sovereignty in its essence is putting the people and their interests at the heart of food production.

"food sovereignty focuses on the rights of people to define their own food methods and places food producers at the core. As for the circumstances of production, it highlights social and economic justice as well."

Some people arguethat agroecologically produced food is expensive and that the goal of cultivating modified seeds and using chemicals is to produce more food to meet population demand. What is you respond to such a critique?

This is a common misconception. Food produced through agroecological practices is actually within market prices or sometimes even less. One reason for this is that many of the expensive company-produced agricultural inputs are not used in agroecology. Those inputs, such as chemical pesticides and fertilizers, and genetically modified seeds, constitute more than 50% of production costs. Agroecological farmers do not need chemicals, nor genetically modified seeds and they use less water in farming, which would save them a considerable amount of production costs, therefore they are able to sell their produce in a reasonable and just price for them and the buyers. There is a misunderstanding or a kind of ambiguity about the difference between agroecologically produced food and “organic products”. Although both are similar in terms of the agricultural practices used and the quality of the food (i.e. healthy and chemical-free), organic products require certifications to be officially labeled as such. This often results in high costs for farmers as the certification process and the certificate itself are costly, thus resulting in higher priced products. That is why it is widely perceived that organic products have a higher price than the market price, and with this comes the presumption that agroecologically-produced produce have higher prices. In reality, agro-ecologically-produced food does not require official certification, as people adopting the mindset and practices of agroecology reject the monopoly or control of any certifying body and rather rely of relationships of trust between producers and buyers.

In Palestine, because of the high costs, the average small-scale farmer is mostly unable to have his/her farm organically certified. Consequently, he or she will have two choices: either chemical farming or adopting the agroecological way of producing food. What some farmers often fail to recognize is that with chemical farming, buying chemicals is putting a financial burden on them, which is why they often find themselves in debt at the end of the season when selling their produce at market price, for which they have no other option. We have talked to many farmers using chemicals in Palestine and have yet to find one who is not in debt. In contrast, when talking to agroecological farmers, they tell us that they are not in debt and actually have quite a good amount of profit, while maintaining a constant reasonable price for their produce, often within the average range of market price.

Additionally, most of the time, agroeological farmers rely on direct purchase of their produce, through selling locally at the farm, or in close proximity to it, or selling them at farmers markets, directly to buyers. This cuts out the intermediary or trader, who often takes a large portion of the profit, which enables farmers to sell their produce within market prices.

Lastly, as mentioned earlier, agroecological farming produce a variety of crops in the same plot of land, as opposed to one type of crop produced via chemical farming. According to many agroecology farmers, the productivity of the land through agroecology is three to five times higher than that of chemical farming, when taking into consideration food production as a whole (including the different varieties). Thus, there is a misconception that production of food using chemical inputs (fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, etc.) yields more quantities. This is not to mention the high difference in nutritional value of the same type of crop when cultivated agroecologically vs chemically.

“Food produced through agroecological practices is actually within market prices or sometimes even less. One reason for this is that many of the expensive company-produced agricultural inputs are not used in agroecology…We have talked to many farmers using chemicals in Palestine and have yet to find one who is not in debt. In contrast, when talking to agroecological farmers, they tell us that they are not in debt and actually have quite a good amount of profit, while maintaining a constant reasonable price for their produce…”

How do you convince “conventional” farmers to turn to agroecology?

With regards to farmers practicing monoculture and using chemicals for a long time, it is clear that they need to see evidence that agroecology is profitable within their specific context. We try to expose them to different experiences in agroecological farms and explain the financial models to them, in addition to highlighting the ecological, political, cultural and health impacts of such models. We engage in discussions on how they are successfully being practiced in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. In the West Bank, agroecology is being practiced in a variety of locations and climatic conditions, even if at a small-scale. However, for example in some areas such as the Jordan Valley, we definitely need more model farms to show that it also works in dry high-temperature environments. There is already one farm there, but we need more of them to convince farmers using chemicals that agroecology can be implemented on a larger scale.

After hearing about the advantages of agroecological farming, I would like to know more about the groups that adopts this concept. Who are they and what are their reasons to support this alternative way of farming?

Different age groups are adopting agrocecology in Palestine. We have noticed that stay-at-home moms in rural areas, who usually have home gardens, find it useful to farm and at the same time care for their children. When given the opportunity to know more about agroecology and its returns on the health of their families and on their household economy, women actually become the leaders of this kind of agricultural production.

We also observe that there is enthusiasm by the younger generation that wants to find alternative means of employment and ways of living as well as to reconnect with the land. They are often university graduates who either were not able to find a job or do not want to be bound to a monotonous job. This wish is often combined with political beliefs and a sense of responsibility to contribute to Palestinian self-sufficiency and sovereignty, often perceived as a means to liberation. So, they revert to this kind of farming, and they dedicate their efforts to learning and experimenting with clean farming and community-supported agriculture. They are also exploring ways to revive the culture of cooperatives and collectives, which previously thrived in Palestine before the influx of aid and NGO sization, which turned most of the cooperatives to rigid formal hierarchical entities and diverted their work away from their original role of supporting the social and economic fabric of Palestinian communities and grassroots mobilization. A number of agroecological farms now are administered by more than one person and the group members are sharing resources and revenues with one another.

With regards to the scarcity of agroecological farmers in the Jordan Valley, what are the reasons people do not want to start a new farm there?

Well first, restrictions by the Israeli occupation on access to water is the main issue, in addition to restrictions on access to lands, which are mostly classified as Area C[5] in the Jordan Valley. There is always this risk of having your land grabbed or destroyed by the Israeli military in the occupied West Bank, but more so in Area C, which is under the occupation’s full military and administrative control. Those restrictions make it extremely difficult to farm in the Jordan Valley, no matter which farming methods are being practiced.

That being said, we should always fight for our rights to access and control our water sources and lands in those areas. I believe this should go in parallel with practicing agroecology, which minimizes the use of large quantities of water resources, which are largely illegally confiscated by the occupation. To confront this, farmers and local communities have adopted simple water harvesting techniques that do not necessarily require big structures, which is also restricted by the occupation in the Jordan Valley.

In my opinion, there should be more efforts at the Palestinian government and civil society organizations to support farmers in the Jordan Valley to stay on their land and face the extremely harsh circumstances. This could partially be addressed through supporting agroecological farming practices that do not leave farmers indebted their entire lives to agrochemical traders. This is a real problem in the Jordan Valley, to an extent that this eventually causes many farmers to leave their lands and seek other means of income generation, often as laborers or farmers in illegal Israeli settlements.

“There should be more efforts at the Palestinian government and civil society organizations to support farmers in the Jordan Valley to stay on their land and face the extremely harsh circumstances. This could partially be addressed through supporting agroecological farming practices that do not leave farmers indebted their entire lives to agrochemical traders.”

Besides the water issue, are there other examples of challenges when trying to collect resources for a farm?

In many types of farming, there is a need for external resources. This makes farming especially difficult when living under occupation and having to import all resources through the border controls of the occupying power. Agroecology provides farmers with practices that free them from relying on Israeli means in terms of importing chemicals or buying chemicals, either from Israel or from abroad. One of the main pillars of agroecology is to give the farmer the biggest amount of autarky possible.

Another big issue that the Israeli occupation is posing is connected to the seeds used in farming. Israel is flooding the Palestinian market with modified seeds, and I believe this is yet another way of controlling food production in Palestine. Often times, Palestinian local seeds are bought by Israeli companies, they genetically modify and patent them, then sell them back to Palestinians. One of the main pillars of agroecology is saving our own local seeds. This provides our farmers with the freedom to cultivate their own varieties without being affected by when Israeli companies provide the seeds or accompanying chemicals. This way, we tackle the issue of control by the Israeli occupation. I believe that the way to full sovereignty is long; they can destroy our structures whenever they want to, so we need to build and accumulate on our knowledge.

In my visit to Om Sleiman Farm, I saw some plants with a label by the Palestinian Ministry of Agriculture (MoA). What is their role in supporting agroecological farming and how do they perceive the trend?

The MoA provides certain varieties of plants to farmers, mostly olive and fruit trees, not necessarily vegetables. However, they need to put more effort in supporting people working in agriculture. What is really needed is a national seed bank. There are a few initiatives for preserving local seeds, but I think it is the role of the MoA to widen their scope and establish a national one. Second, the budget of the MoA is really small. Therefore, there is a need to rethink the budgets for the ministries that are providing basic services and that are supporting production in the country. Agriculture is one of the main sectors that they should focus on. They also should concentrate on providing farmers with incentives to farm in Area C, even under the threat of the Israeli occupation and reduce taxes to incentivize them. It is vital to support farmers who decide to take up this career in spite of the challenges mentioned, rather than saying “this is Area C; we cannot do anything about it.” The MoA should also activate their emergency funds for farmers to support them in times of need, natural disasters or attacks by the Israeli army in a way that is more sustainable. Moreover, I think the MoA should focus on a strategy to map all kinds of agricultural production in order to find gaps in production, from a self-sufficiency perspective, and fill them accordingly. They should also provide extension services on natural methods of pest and disease management as opposed to the use of chemicals that are destroying our land that is unfortunately shrinking as a result of the occupation’s policies of confiscation and annexation. There is a lot to work to be done by the MoA and we as an agroecology movement call upon them to adopt the methods of agroecology. They should work to instill the values of being able to produce our food with our own local resources.

I can see why people would refrain from farming in Area C. If we look at the recent numbers of people working in the agricultural sector, we can observe that it is shrinking. Did the work of agroecology and food sovereignty activists change this trend?

In 2015, I worked with a friend of mine, Dr. Muna Dajani, and the Heinrich Böll Foundation – Palestine and Jordan Office to produce the Conscious Choices Guidebook. One of the sections of this publication focused on food production, local producers and farmers. When we developed the second edition in 2020, we witnessed a substantial increase in the number of farms adopting agroecology as well as increased interest in agriculture by the younger generation. To a large extend, this is a result of the tremendous work done by agroecology activists in Palestine.

We can see a global trend of people moving from their village to the city in search of a job that is viewed of higher social and economic status as opposed to farming, which is sadly considered nowadays of a lower status that does not fit a “modern” lifestyle. However, in parallel, we witness a growing movement, especially of younger people, who are refusing this lifestyle; it does not represent who they are or fulfill their purpose. They want an alternative and are searching for their own calling. We need to support this movement of young, motivated and productive people in order to create sustainable change. They need a supportive environment in order for them to feel safe when choosing an alternative way of life.

What is the role of Dalia Association in order to create a supportive environment for young farmers?

Dalia Association tries to support in a number of ways: The first is knowledge production. We produced a research paper on Palestinian National Food Sovereignty in Light of the Colonial Context and one on Status of Farmers in Border Areas in the Gaza Strip from a Food Sovereignty Perspective. We also produced a short documentary titled "Untold Revolution" on the growing agroecology movement, which is the first documentary about this topic in Palestine. Recently, we published a compendium of articles titled “Our Heirloom Seeds”.

The second way is participatory grantmaking, by supporting agricultural initiatives and cooperatives that are gearing towards agroecology. This is done through trainings and workshops on agroecology and food sovereignty, exchanges, and by providing grants to them.

The third is practicing agroecology at Dalia Association’s premises, where the garden is utilized to provide training on agroecological techniques, and was recently turned into a community garden managed by community members who were involved in the trainings.

Lastly, on the advocacy level, we have approached different Palestinian ministries, especially the MoA, and have developed a position paper directed at them and calling upon them to adopt policies in support of agroecology and food sovereignty. However, this needs more than one paper or one discussion, but is rather an ongoing one. Some of the officials at the ministry did not know what Food Sovereignty even was at first.

Untold Revolution: Food Sovereignty in Palestine الثورة غير المحكية- السيادة الغذائية في فلسطين - Heinrich Boll Foundation - Palestine & Jordan

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTube

Food sovereignty is a term that is used in many different regions, especially South America and India. Do you try to connect with communities or community organizations globally to talk about food sovereignty and agroecology?

Dalia Association is part of some global networks, mainly community philanthropy networks. Dalia Association itself was established over what we perceived as an influx of conditional aid, that is mostly not helping on the ground, but rather pushing certain agendas and a “westernized way” of development, rather than tackling the issues and real needs of Palestinians – not merely trying to push for and end of the occupation. From this sense, we are connected to different community philanthropy organizations around the world and some of them are working on food sovereignty, mainly in the global south. Also as a volunteer, we co-created, the Palestinian Agroecological Forum, which is also part of a wider network in North Africa and West Asia. We are collaborating with different entities and movements on food sovereignty, so we are definitely connected to global networks in this regard.

What kind of advantages do you see in connecting to other global food sovereignty actors?

Well, it is more of feeling that you are part of a wider, global movement, calling for our rights as people to regain our food production methods and to control our food systems. When working in this field, you are facing many challenges related to the capitalist logic of our market system and in Palestine, the Israeli occupation, conditional aid by international donors and the adoption of a free-market approach by the Palestinian Authority. The feeling of being part of a bigger movement gives us moral support, which is much needed. In this context, we exchange knowledge and expertise with different actors that is valuable for our work. Financial support can also be gained by connecting with actors around the globe, but I see this as the least important part of our international networks. The moral support and the knowledge exchange is most important to us.

[1] An international movement that consists of many small- and large-scale farmers, rural communities and agricultural workers all around the world.

[2] Agroecological farming refers to a form of agriculture that is sustainable and chemical-free, using efficient agricultural methods to grow a variety of crops in the same location

[4] Monocropping is the practice of cultivating only one crop year after year on the same land.

[5] Area C is a classification under the Oslo II Peace Agreement between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). These areas were supposed to be “gradually transferred to Palestinian jurisdiction” following the five-year interim period, however this never took place and these areas, which constitute over 60% of the West Bank, remain under Israeli military and administrative jurisdiction.