It is an adage of the times that “information” is “power”. Under these terms we immediately think about information as numerical units, statistics, quantities and a wide range of computable data, which can later be used to take strategic decisions.

Information, Numbers and Agro-Resistance in Palestine[i]

Information is never neutral

It is an adage of the times that “information” is “power”. Under these terms we immediately think about information as numerical units, statistics, quantities and a wide range of computable data, which can later be used to take strategic decisions. While this would not be an incorrect statement, it is also just half the truth. For information has to be understood as patterns, traces, configurations, representations or displays. And what are these patterns about? How is it that these representations are representing something? Well, they are recollections of pieces, which aim at reconstructing what once was. In other words, if patterns bring together numbers, these numbers are abstractions already, from actions, from habits, from actual events that once took place, or are taking place right now.

Nowadays numbers are mostly understood as abstracted figures serving a function in a mathematical matrix, but there was a time when numbers were thought to be spirits, essences wandering the surface of the earth. Our informational episteme equates information with numerical figures, specific and concrete units that stand in place of a given reality. But these numbers are reductions in a system already, and not the numerical symbols that once tried to convey a given narrative. The difference is subtle. However scientific or objective our mindsets, we all accept that a number is an imaginative construct. And in this sense, it is already a translation, a representation that is used in a powerful processing machine (the mathematical languages) to explain a reality, shaping it after a formidable myth. Or as Federico Campagna phrases it:

Coherently with its status of offspring to measure, a piece of information actually refers only extremely tenuously (if at all) to the ‘thing’, which it is supposed to describe. Indeed, the contemporary interest in their supposed referential relationship between information and things is ultimately a nostalgic form of superstition.[ii]

While Campagna rightly describes the process of technical instrumentalization of the world around us, we could contend that we could indeed try to reconstruct the “thing” that preexists the number, to try to reverse the reductive status and regain the precise moment of its translation, its metamorphosis, its operative in-betweenness. This would imply as much as tracing the genesis of those units, to accompany them as they are being transformed, concocted. For if we understand and participate in the re-articulation between a reality and its abstractions (never loosing ground between both, and always considering that we are the living link holding both together), then we can invest numbers with a different information value, inserting key elements in a form of active social knowledge. Such a knowledge (as I will try to argue in this article) would be composed of valued and symbolic representations that inform us about a shared reality.

An active social knowledge contends the notion of information as an accumulative machine, where inquiries are turned into scales, measurements, averages. If we know how this machine works, how it alters subjective approaches into objective masks (think of such economic measurements as “consumer trust”, or the domain of “polls”, or the latest development on the democratic notion of “approval rates”), then we can use our own, intersectional sources as legitimate inputs too. This does not imply the forging of facts or an attempt to build up another statistical frame, but it is itself a frame that acknowledges the qualitative traits of numbers, where they reflect a given worldview, a cosmogony.

In this sense, numbers can be used as symbolic codes, allotting a different informational value that can then be used to encode common actions, share dynamic perceptions and mobilize a common agenda. With this framework in mind, the following wants to become a feasible and yet very synthetic program to come closer to this ideal.

Six steps to turn patterns into flows

I will elaborate here on a practical route to think about numbers and information beyond the model of an accumulative machine, and more as a possibility that enables the mobilization of common efforts and aims for the production of first-hand, community-based information. An essential stage for this is identifying a collective goal, to which all data gathering efforts can orient. Additionally, the value of information needs to be socially recognized beyond the idea of numbers as neutral figures, to consider them as indexes about the world we are creating, as markers on a fluid route. I first developed this approach as a socially engaged artist with the Nerivela Collective, in Mexico City, during a series of neighborhood-based activities that tried to generate knowledge about the state of the habitats of certain communities between 2013-2015.[iii] Writing from Palestine, this article imagines a particular, context-specific implementation: the “Labeling Agro-Resistance” project (from here on LAR). The specific problem I wish to zoom in is the state of water apartheid in Palestine[iv], and to imagine ways to build on the consciousness and momentum of the contemporary agro-resistance initiatives[v] in the West Bank. The projects that informed and inspired this text are mainly the “Palestine Heirloom Seed Library” in Beit Sahour, “Sakiya” in Ein Qiniya, the pioneering role of agronomist Saad Dagher and other individual efforts, such as Dragica Alafandi’s roof garden in the Dheisheh refugee camp, near Bethlehem. The proposal described here does not pretend to be a definite solution or a risk-free development to ongoing practices. It is just intended as a sketch for a possible step that could be implemented, but which would need to be –in any case– socialized and further developed with the relevant actors.

First step – Observe obsessively, recognize the problem, set the field.

The first step in the process is about grounding the forces, establishing the field. We will always be at the center of the observation, but we need to understand how we relate to the world with and beyond us (the Heideggerian being-in-the-world states this idea at its best). So in this sense, what is a field? As John Berger states: “The existence of the field is the precondition for [events] occurring in the way that they have done and for the way in which others are still occurring.”[vi]. However, the field is also temporal and can be an event, one that stands in dialectical relations to others and yet is in itself a requirement to them all. The field only arises when we open ourselves to it, when we sense its constituting elements – on the brink of being sorted out, organized, constructed – and its compelling strains. Otherwise, the place of action remains a trivial space, a pseudo-neutral Cartesian plane where anything passes and means just the same as anything else.

For the LAR idea, the recognition of the situation – i.e. setting the field – needs to acknowledge that anything developed in the West Bank will necessarily take place within the framework of the Israeli military occupation. Water scarcity is not a natural condition (on the contrary, water is abundant in underground aquifers), but it is a human-produced system of control and active dispossession. And yet, there are some elements through which it is possible – at least theoretically and imaginatively – to create different ways of making. Power is always a relation, and even from a position of weakness it is possible to reorient the stakes (though not necessarily the outcomes). In this sense, water is to be acknowledged as a central trope in the field, a crux of metaphors out of which to organize a tactical rhetoric and a specific set of demands.

Second step – Relate yourself to the phenomena.

Once we acknowledge where we stand, we need to find the connections on the field, the figurations traversing the events and particular spatial demarcations, the articulations and kinds of socializations that render a phenomenon its actuality. We can never forget that all these connections traverse us: we stand in the vortex of meaning. In other words, there is never a lineal causation that is absolute. Connections, relations and meanings are all relative and they materialize through use values, i.e. standards and principles that are triggered under a given frame. Karl Marx misunderstood the idea of “use value” as a sort of grounding for an economic structure, and that move divested the broad possibility of the concept. With the critique of this Marxist notion in mind[vii], use values must be seen as articulations of social relations that compose a dynamic system of meaning. Everything that exists in the human world exists as an expression of a social (use) values. This understanding is essential to set up our own personal and very real experiments.

For the LAR idea, this second step has already been implemented by agro-resistance projects in Palestine, which are aware of the use value of each of their resources, including water. They have already asserted the importance of self-sustainability under the state of continuous structural aggression by the Israeli occupation, and have configured schemes to circumvent, at least partially, the control over food and other crucial commodities. In this context, the use value draws from the possibility of growing local produce as a means to survive, and to assert the right to an autonomy and an identity. The named projects and initiatives draw from a history of uprisings[viii], and are aiming at the long term to become a beacon of hope for a possible future.

Third step – Numbers can be emotional too. Translate the world onto them and back.

Whenever we are pursuing something, we are thrusting creative forces onto the world. This can be as basic as craving ice-cream, and then producing the trajectory, the time allocation and the micro economic dynamic that leads to a chosen flavor (i.e. support for the industry of strawberry, chocolate, etc.). This is why some sociologists refer to us the agents as “prosumers” instead of limiting us to “consumers”[ix]. These so-called consumption choices (with their tactics, strategies and all their lore) are at the base of our creative potential. When we decide something, we take sides. We affirm worldviews and ideas; economic, political, environmental and cultural trajectories and programs. By this third step we know that we participate in the creation of worlds, influencing the socio-spatial dynamic by implicating ourselves, starting from the moment of the adoption (consciously or not) of values and associated meanings. All these affirmations can be measured, a numerical value can be allocated to a given preference, producing thus arithmetical traces. Hence, what are we affirming with our habits from which a form of information and numbers arise? What are we mobilizing? What are we demanding? Numbers can encode specific narratives if we know how to write and read them, stories that speak about our trajectories and our demands.

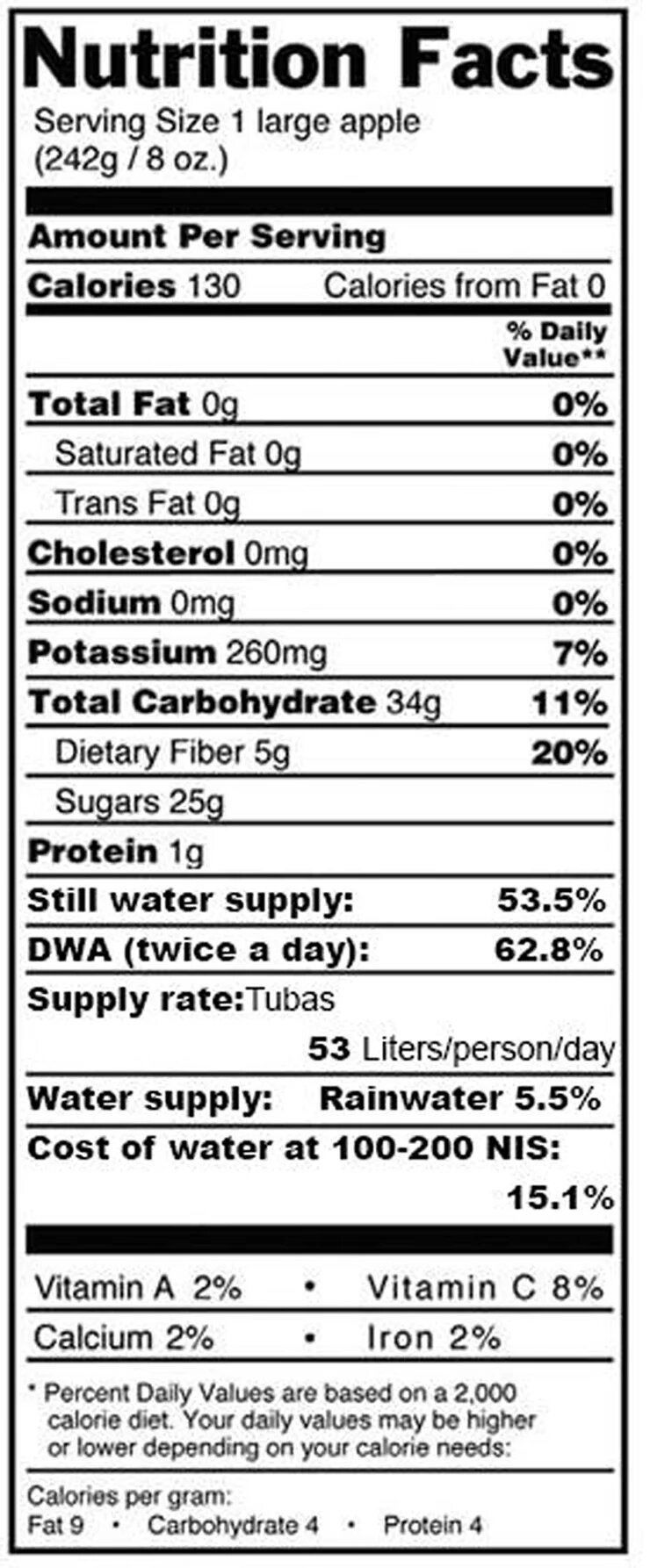

For the LAR vision of giving visibility to the loci and conditions of agricultural production as acts of resistance, the plan is to include specific information as part of the nutritional values. That is, first, to professionalize the labeling of nutritional facts in order to clarify what the everyday ingestion of these vegetables means in relation to our own bodies. And second, to expand on these values to include information that is vital for influencing the diverse logic-behavior dynamics and patterns in relation to the reality of water apartheid. For example, what is the cost per liter in the area? What well or spring is it coming from? How many days a year is there a shortage of water in that area? The idea is to produce new procedural, number-based (i.e. indexed) ‘common denominators’ that tell the stories of agricultural production in Palestine as they unfold under the colonial condition, and to inspire new kinds of ‘social contracts’ that draw from the active social knowledge. These processes depend on the ability to express and connect specific stories of local producers with specific ways to act upon the information; one that takes the relationship between producers and non-producers beyond the mere momentary exchange/consumption of the material object.

Drinking Water Supply: 53.5% – How much water is supplied in the region

DWA – Discontinuation of Water Access (twice a day) : 62.8% – How many people live with interruption of water supply two times a day in the region

Supply Rate (the example of the town of Tubas): 53 liters per person per day – average supply of water in the region

Water Supply: 5.5% – Where does the water come from in the region

Cost of Water at 100-200 NIS: 15.1% – Percentage of the population that pay just between 100 and 200 Israeli Shekels on the region.

Example of labeling for natural products

Source: https://www.makeuseof.com/tag/7-websites-give-nutritional-information-e…

Fourth step – Watch the numbers perform.

The creation of new narratives through this approach to index-based information will create multiple perspectives. Directing these perspectives towards progressive action is a function of time. Numbers, averages and indicators can be planted and harvested. With time, these can produce new modes of social interpretations and use values. The experiment will have a life of its own. The field is active. Follow the storyline. What happens is what is: observe it unfold and watch the numbers perform.

For the LAR vision, the success relies very much on whether a network of producers can identify a given set of values and translate them into a notation, an index, a number that can be transmittable to the final prosumer. This means that it would be necessary to meet, read and arrange the data, discuss the outcomes together, debate around their social value and their specific need, etc. The numbers are the language, the encodings, and these are the core of the agenda-setting behind the LAR, which should aim to be inclusive and open for continuous reassessment by and with the communities and their networks.

Fifth step – Be playful, tailor numbers to a form.

If one understands the ‘performance of the numbers’ in relation to unfolding happenings, then it should be possible to tailor a form – be that a narrative, an archive, a symbolic or real space. This would constitute a materialization of a social use value through a discourse of measurable changes, where we express a world(-view) and at the same time help re-shape it. The social labor and collaborative investments should be re-directed to the process itself, so that they can feed the necessary loops of participation over time. The form is the kind of collective experiences that were created through the encoding and decoding of numbers, and the traceable information that makes an impact. This is the core of an active social knowledge in the making.

In my imaginary of LAR, the community-produced numbers engender new kinds of statistics, graphs and systems of representation that tell the history behind the vegetables, the fate of the laborers, the land and the water that were needed to generate life and the particular produce. Understanding the complex and multifaceted dimensions of the environmental conditions in Palestine cannot happen while ignoring or assuming a short temporality for the Israeli military occupation. However, LAR is an imaginary where through the involvement of the many, it becomes possible to narrate how Palestinian agricultural production stands in spite of the colonial condition as a resilient force, as it is people, with their everyday choices, that determine the continuity of such acts of resistance.

Sixth step – Re-appropriate the form, celebrate small politics.

In this final step, I imagine one would have the keys, the coded information, to trigger particular events. This information is by no means a secret, but it is a local “recipe” that is highly contextual to the field, involves communities and evolves with time. At this final stage one would be able to identify and connect further social values to the process, to measure achievements and shortcomings, to count participating prosumers, days gone by, investments and other resources. Information is power. So far it has been mostly employed by capitalist and neocolonial systems of dispossession of resources, geographies and narratives. Yet it can also be used to counter them. Essential to creating the counter critical mass is mobilization of rooted solidarities that materialize through action; in this case via the production of numbers for a different approach to information, one which turns patterns into resilient flows. Hence it is important to share stories and discuss emerging forms, and along the process, celebrate the successes of small politics.

My imaginary LAR is situated in a deeper historical narrative, one that takes into consideration the kinds of community projects and mobilizations around water and agriculture in recent history, during the First Intifada, during the events of what became known as Land Day since 1976, and the voluntary work committees in refugee camps of that era of Palestinian resistance. These kinds of agro-resistance initiatives have not ended the military occupation, but their success cannot be measured in those terms. Rather, they should be discussed around three notions; first, on their capacity to maintain a sumud (state of resilience, steadfastness) therefore a key to safeguarding socio-political values; second, on their ability to produce collective networks, know-hows, and active social knowledge; and third, by the traceable, measurable impact on changing discourses based on information and critical, collective puzzling of possibilities and solutions. And in these three dimensions, agro-resistance initiatives in Palestine are a pivotal domain in the Palestinian quest for justice. The recognition of common achievements and their translation into inspiring narratives – even if temporary – is necessary to encourage a continuation in spite of growing difficulties. I hope, one day, that LAR becomes a reality, thriving and living a life beyond my current imaginaries, however long or short that might be.

This is an article from the “Takhayal Ramallah” project conducted in 2019 with UR°BANA and Sakiya.

[i] I want to thank the editors Natasha Aruri and Sahar Qawasmi for their helpful remarks, addenda and comments. A special thanks to Ana Luisa Ramírez, partner in many adventures, for helping me adjust the images that illustrate this article.

[ii] Campagna, F 2018, Technic and Magic. The Reconstruction of Reality. London, Bloomsbury Academic, p. 81.

[iii] For more details, visit the corresponding site (in Spanish) available from: http://mumo.nerivela.org/category/indicadorese/ [8 October 2019]

[iv] There are abundant sources for this topic, but I will focus on a primal one: World Bank 2018, Securing Water for Development in West Bank and Gaza : Sector Note (English). Water Global Practice. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/736571530044615402/Securing-w… [8 October 2019]. Most of the data informing this proposal can be found in this report. Therefore, due to space restrictions, sources for individual figures will not be independently quoted.

[v] Agro-resistance means here practices of agro-ecology aimed at attaining food-sovereignty in Palestine and linked to struggles for self-determination.

[vi] Berger, J 1980, ‘Field’ in About Looking, New York, Pantheon Books, p.192-198, here p. 197

[vii] A critique of the Marxist notion of use value in this sense can be found in Baudrillard, J 1981, For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign, trans. Charles Levin. St. Louis, Telos Press. Also, notably, in Jameson, F 1991, Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Durham, N.C., Duke University Press.

[viii] A very popular example is the dairy farm in Beit Sahour which produced milk for the community during the First Intifada, based on which the documentary The Wanted 18 (Amer Shomali, Paul Cowan, 2014) was produced. Another example is the Palestinian Agricultural Relief Committees (PARC).

[ix] Michel de Certeau calls “ways of doing” the practices through which users re-appropriate for themselves the space organized by the technicians of sociocultural production. See De Certeau, M 2000, La invención de lo cotidiano. Artes de Hacer, Trans. Alejandro Pescador. México, Universidad Iberoamericana, p. xiv

-------------------------------------------------------------

Captions:

IMAGE1 and IMAGE3

Added information:

Drinking Water Supply: 53.5% - How much water is supplied in the region

DWA – Discontinuation of Water Access (twice a day) : 62.8% – How many people live with interruption of water supply two times a day in the region

Supply Rate (the example of the town of Tubas): 53 liters per person per day – average supply of water in the region

Water Supply: 5.5% - Where does the water come from in the region

Cost of Water at 100-200 NIS: 15.1% - Percentage of the population that pay just between 100 and 200 Israeli Shekels on the region.

IMAGE 2

Possible implementation

Example of labeling for natural products

Source: https://www.makeuseof.com/tag/7-websites-give-nutritional-information-e…

----------------------------------------------------------------