What Ramallah is experiencing in terms of the current political stagnation, sharp economic inequalities, and the real estate boom is having major impacts on the city’s urban and environmental deformation and destruction .

The issue is, decolonisation means alternative economies

What Ramallah is experiencing in terms of the current political stagnation, sharp economic inequalities, and the real estate boom is having major impacts on the city’s urban and environmental deformation and destruction . Meanwhile, much of the current local governance policies are framed towards maintaining the Palestinian municipal economy as an ephemeral one through World Bank forms of incentives. This is consistent with the colonial strategies of systematic destruction of cultural landscapes, natural resources, and exacerbating uncertainties and precarious realities.

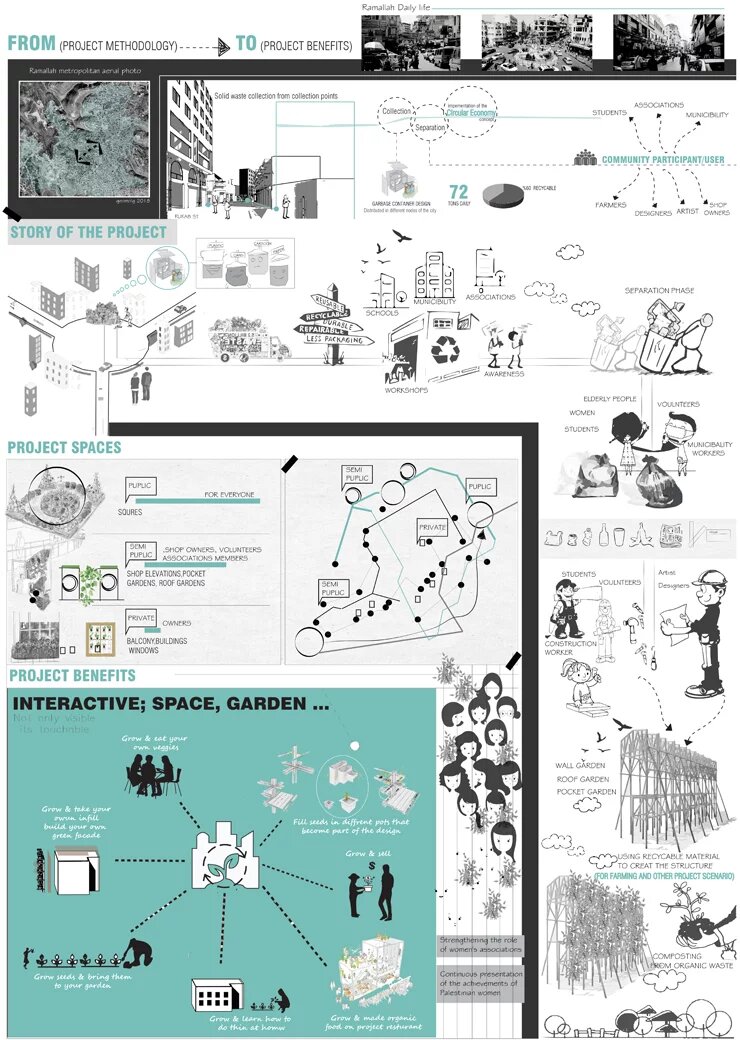

Nonetheless, some community campaigns have succeeded in reducing environmental impacts and preventing the aggravation of such problems in different areas in Palestine. For example, there was a campaign in Ramallah that succeeded in getting people to separate paper waste and sold it to cardboard factories. But sadly, it stopped after short while because separated paper waste was being collected and disposed of along with other kinds of waste in the landfill of Zahrat al-Finjan. While the city produces nearly 72 tons of solid waste daily, recyclable waste is 60%.[i]

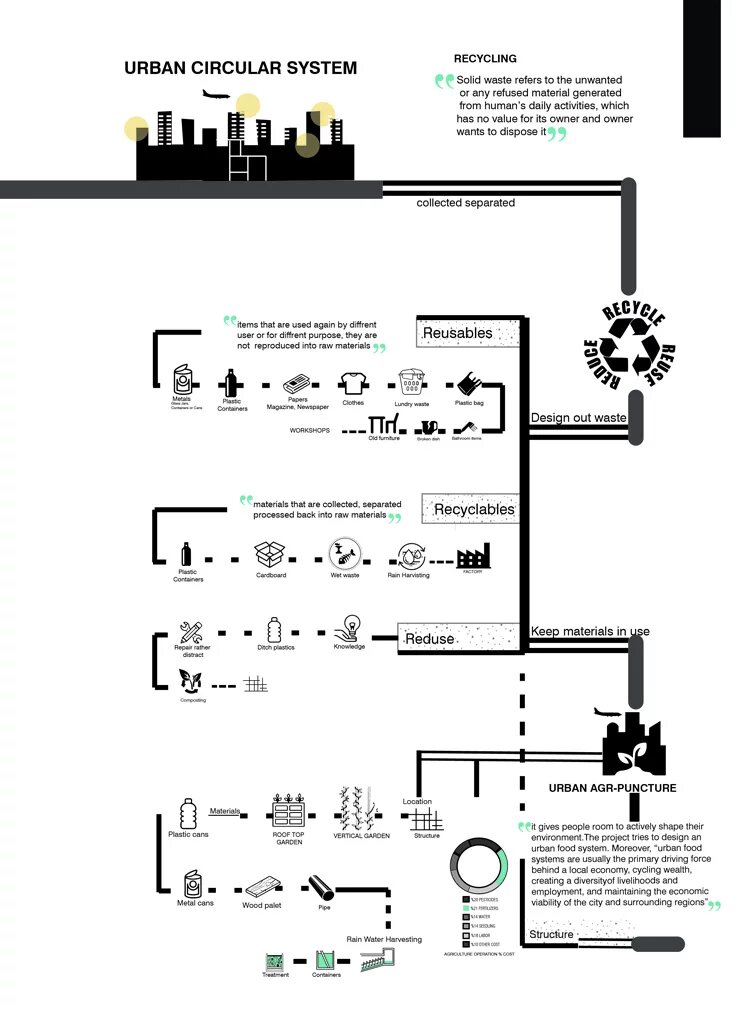

This contribution to Takhayal Ramallah sheds the light on communal practices that are considered the cornerstones toward establishing a circular economy, where resources and waste are looped in the city. Following the Urban Circular Economy guideline that encourages projects to work through these main principles, here we first start with thinking about how to “design out waste” in the city; i.e. social and economic operation cycles that include reusing, reducing, and recycling solid waste (plastic, cans, cardboard, wet waste, fabrics). The second principle is “keep material in use”, and in our future we imagine this being fulfilled through mobile Agri-Puncture structures. We see these as produced from locally recycled waste, and would serve at different nodes in the city; as a vertical garden, roof garden, or a pocket garden. The last principle is “regenerate natural systems”, which we will fulfill through designing the structures to harvest rainwater and therewith addressing the water problem in Ramallah[ii].

Imagining how Ramallah could be like under such a scenario, we see Ramallah’s center becoming a dynamic showroom for possibilities on how the city can take on a skin of green structures, arts installations, local produce, etc. We see it as a place where agriculture meets a new collective culture of urban identity formation in the cityscapes by many actors; schools, municipality, social organizations, artists and equally independent individuals all share the right to exercise their abilities in continuously re-shaping and re-adapting their own city.

Circular Economy: concept and principles

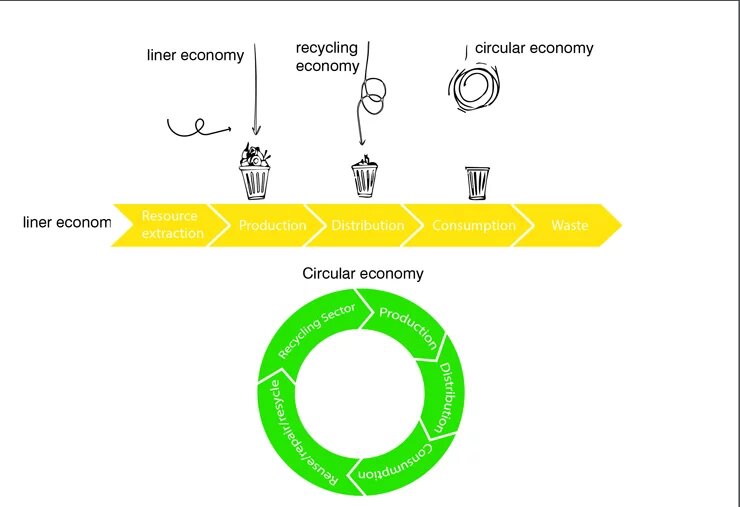

The concept of the Circular Economy (hereafter CE) has gained momentum since the late 1970s [iii]. Webster states that “a circular economy is one that is restorative by design, and which aims to keep products, components and materials at their highest utility and value, at all times”[iv]. Here we look beyond the traditional linear economic model of 'take-make-consume-throw away' to resources (see figure 2). This means that raw materials are used to make a product, and after use any waste (e.g. packaging) is thrown away. In an economy based on recycling, materials are reused. According to Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a circular economy “builds long-term resilience, generates business and economic opportunities, and provides environmental and societal benefits.”[v].

The multiple definitions mean that there is no official standard on how circularity is measured, and it can vary in implementation in different communities. However, as indicated in the introduction the EMF defines three principles for CE: Design out waste and pollution; keep products and materials in use; and regenerate natural systems. Accordingly, figure 3 explains how we see the process of designing looped cycles in Ramallah; how to reuse and recycle solid waste in order to create the needed and compatible agricultural structures.

Turning waste into work

Every year the waste sector in areas governed by the Palestinian Authority has to deal with an estimated 1.2 million tons of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW), with waste generation still rising. Uncontrolled dumping of MSW is still the main method used for disposal throughout the governorates, in unregulated dumps with periodic burning. This practice has severe health, environmental and socio-economic impacts[vi].

Ramallah exports about 72 tons of solid waste daily at a time 60% of it is recyclable[vii]. Although there were many societal and institutional attempts to find solutions to deal with recycling solid waste, most attempts did not move beyond the waste separation step and have had no real impact on the ground. Therefore, in the future, ideas for better waste management and CE have to consider the limitation of recycling processes in a colonized city like Ramallah, as well as issues of revenues and operating costs in determining what and how to manage SW.

In our proposal, CE will be promoted through highlighting the financial and health benefits for the community; which also has materializations in the city space in the form of the agricultural structures and also through the goods and artistic products made by the community. In environmental terms, whereas today more than 90% of solid waste is directly disposed of in landfills, such a new approach to thinking about what makes up the urban space will reduce this volume. Also, there is a wealth of know-how that individuals will gain in the process of teaching and trying out techniques and methods for those systems and operations, here Figure 4 shows how our project creates opportunities for different layers of the community, puts emphasis on the social-engagement to connect and forge new solidarities, and socio-political agendas.

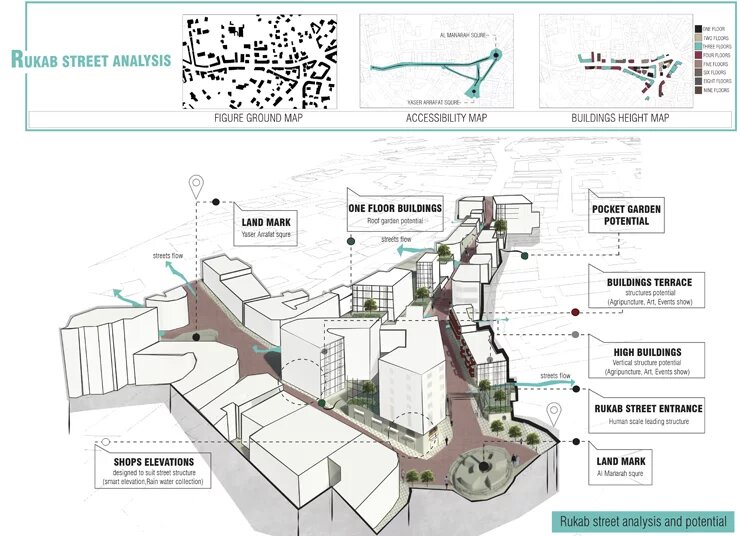

Rukab [Main] Street prospects: Towards an Urban Agri-Puncture

Urban agriculture contributes to increasing the volume of vegetation and reducing greenhouse effect, it creates employment opportunities, and gives people room to actively shape their environment. Therefore, our idea envisions an urban green system following the second principle of circular economy, to keep products and materials in use. By designing cycles for reusing and recycling the city’s solid waste in order to construct structures and provide organic fertilizers, individuals become producers rather than consumers.

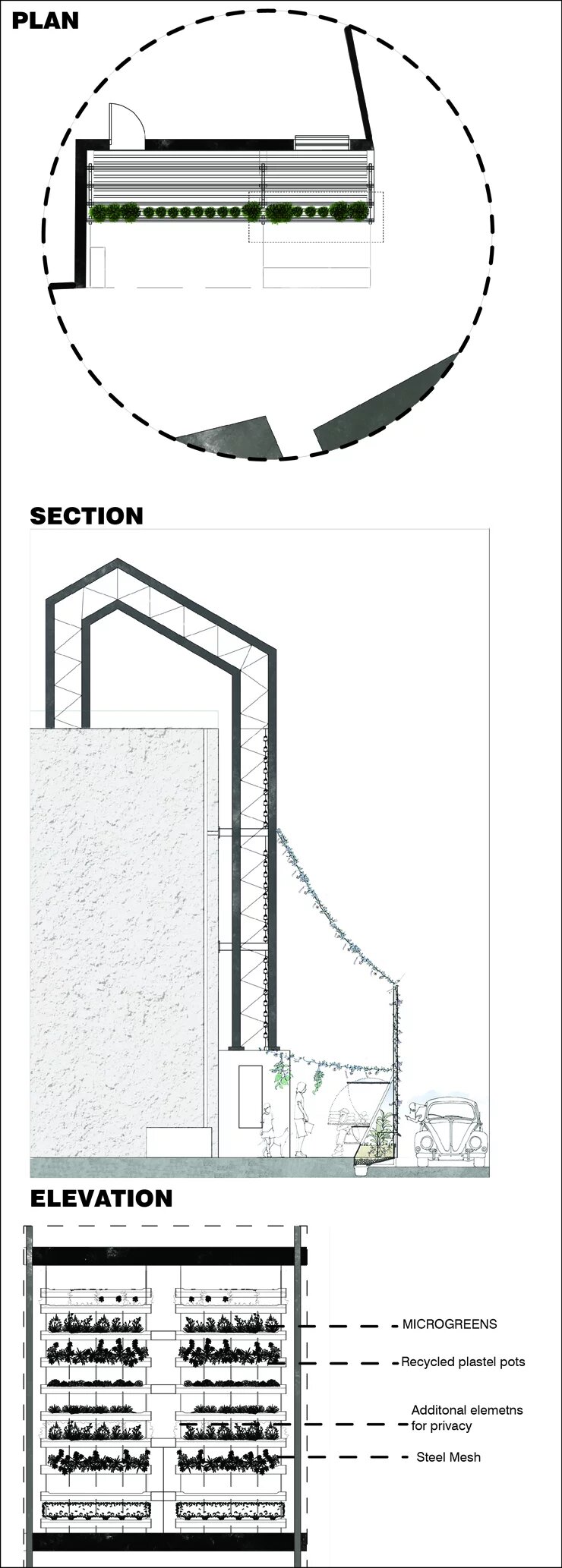

Figure 5 shows an analysis of potential spots at Rukab (Main) Street; which is considered a dense and busy commercial area with not much land available. Some of these spaces are contaminated, others not accessible for urban activities, e.g. socialization, cultural value co-production, etc. Nevertheless, we want to have the opportunity to use the vertical volume of unbuilt (anti-) space, namely, the distinctive surfaces of infinite roofs and walls. In doing so, we apply urban Agri-Puncture which refers according to Vanessa Quirk to “a way of planning that pinpoints vulnerable sectors of a city and re-energizes them through design intervention”[viii]. Rukab St.’s Agri-Puncture will have many forms of gardens and small-scale farms – on walls, on rooftops, on balconies or making new ones. In Ramallah’s Mediterranean weather, not only there are good climatic conditions for such activities, but also, it is a needed measure to deal with the growing pollution (air quality, noise, aesthetics) in the city center and the growing devastating effects of global warming.

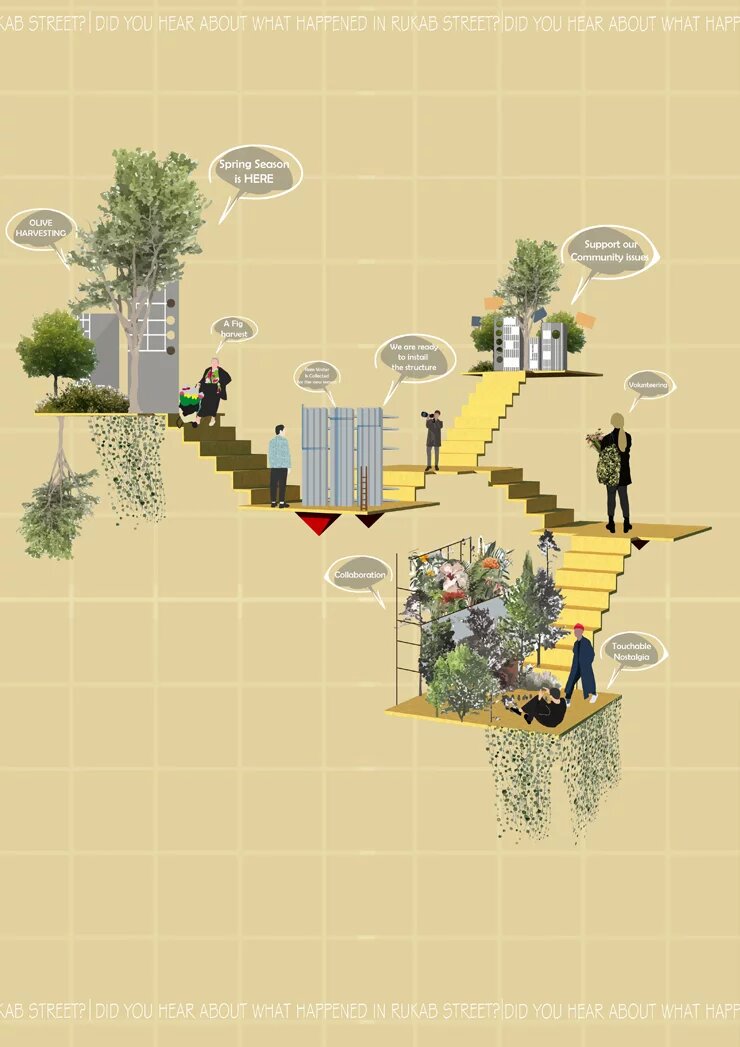

The role of local architects, engineers, artists, farmers and craftswo/men is to work together to design environmentally friendly, easy to maintain and sustainable Agri-Punctures structures that help gain the trust of the community in the idea. To satisfy that, structures have to be dynamic and operational during the different seasons and in accordance with the needs of events. In Figure 6 we show three images of the proposed structure during different times and events; everyday mood, and the beginning of spring. Engineers, farmers, students and artists can work together to design a dynamic structure that accommodates shifting events; social, national, spiritual and everyday mood.

In the close of our imagination we would like to remind that a shift towards the circular economy concept requires new sets of norms and regulations by ministries, the municipality, and the society itself. Nudging people’s choices towards taking up, for example, Rukab St.’s Agri-Puncture, requires showcasing through testing and examples, taking up feedback in following attempts, and introducing the needed legal and administrative parameters to allow and encourage this. This process has to be participatory, inclusive and replicable, and decisions should be made democratically and transparently. We need as a society to get out of our comfort zones, because a better urban future is possible.

This is an article from the “Takhayal Ramallah” project conducted in 2019 with UR°BANA and Sakiya.

[i] Ramallah Municipality. 2019. Ramallah Municipality launches the first pilot project for solid waste separation in new neighborhoods. Available at: http://www.ramallah.ps/ar_page.aspx?id=C578Rqa2584009395aC578Rq [Accessed 28 Oct. 2019].

[ii] The Israeli Occupation controls all of the water resources on the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. They are currently utilizing about 80% of the groundwater resources. They impose strict restrictions on well drilling and construction of water distribution networks. Palestinian farmers have access to 150 mcm per year to irrigate around 10% of cultivated lands, while Israeli farmers enjoy abundant water and irrigate 50% of their lands they cultivate (ARIJ 2015). In areas governed by the Palestinian Authority there are severe shortcomings in terms of planning and actively building systems for rainwater capture, storage and reuse, as well as that of dealing with acute storm water. For more see ARIJ.(2015). The Intensifying Water Crisis in Palestine, http://www.arij.org/files/admin/The_Intensifying_Water_Crisis_in_Palestine.pdf

[iii] Macarthur, F. 2013. What is a circular economy? A framework for an economy that is restorative and regenerative by design. https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/concept?fbclid=IwAR29AV-5_v17DXzleH561FgVwhtab1wlahqN51G7Fbo9iOMBup5LMgdU-Es

[iv] Webster, K. 2017. The circular economy. Isle of Wight: Ellen MacArthur Foundation Publishing.

[v] Towards the circular economy. 2012. Isle of Wight: Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

[vi] JSCSWM. 2015. Solid Waste Management – Ramallah and Al-Bireh Governorate Consulting Services Accompanying Measures to the JSC Investment Programme. https://www.aht-group.com/cms/index.php?id=274&L=0

[vii] See note 1 above.

[viii] Quirk,V. 2012. Urban Agriculture Part III: Towards an Urban "Agri-puncture". https://www.archdaily.com/239677/urban-agriculture-part-iii-towards-an-… and Syntanya, G. 1905. The Life of Reason: Reason in Common Sense. Scribner's