Personal reading of the various aspects involved in moving between two points to write an ever-regenerating memory and a perception that is reshaped by geopolitical changes, day after day.

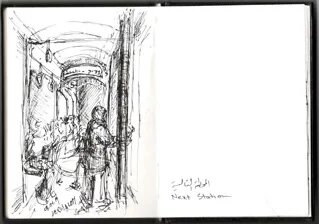

As an enthusiastic listener to all the songs of Fairuz, I have a collection of songs that I particularly like. Fifty continuous minutes of Fairuz songs occupy a small, but important, space in my cell phone’s memory. I usually listen to this collection on my way home from work at Birzeit University to Jerusalem. On the days when there is a traffic jam at the checkpoints of Hizma or Qalandia, I press repeat and listen to the collection one and a half times or twice. Hence you can imagine I have enough time to finish lots of things on the way; I eat the sandwich that I prepared in a hurry while reading a book or writing comments in its margins. I file a nail that was chipped on my way out of the house then move on to check my emails and latest received messages.

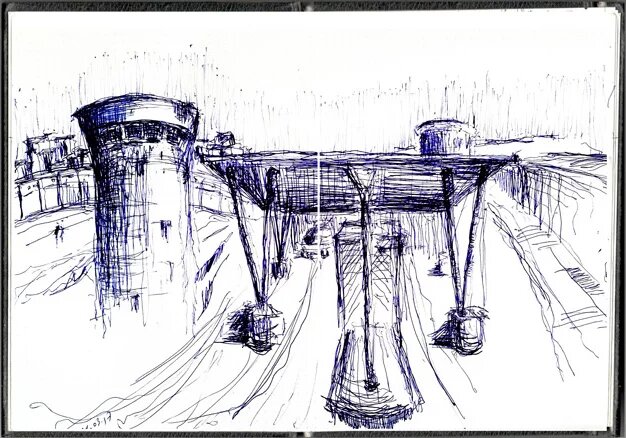

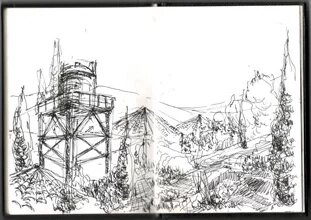

Sometimes, I do none of these things and instead I take out a little black sketchbook from my bag, turn my eyes towards the window and start sketching one of the successive scenes passing in front of the window of the bus I ride these days; which takes me directly from Jerusalem to the university through Hizma’s military checkpoint located to the Northeast of Jerusalem. This was not always the route I took to the university. During the five years prior to my work at the university, when I was still a bachelor student, I used to pass through the infamous Qalandia checkpoint North of Jerusalem, driving through Ramallah until arriving at Birzeit. That meant I had to take three buses instead of one, and a flow of fragmented scenes through three different windows.

Of course, those who know the roads connecting Jerusalem and Birzeit in particular, and between Palestinian areas in general, know how big of a part of a Palestinian’s daily experiences these roads are. S/he also knows that a variation that may seem insignificant, like changing the path between two fixed points, must mean more than the difference in how long or how fast it takes; the matter which became even more evident to me everytime I contemplated the sketches that filled my black sketchbook throughout the past year in comparison to the ones in my older sketchbooks (Qalandiya’s sketchbooks!), and the folded papers inside my university books. I never thought of these sketches as more than an exercise for the eyes and hands, and a way to avoid thinking about the long time I spend on the roads. However, two things drove me lately to believe that these sketches have another dimension: the transformation that occurred on my personal transportation experience, which I started noticing in the contents of my sketches; and, a visit I paid a few months ago to an exhibition at the Palestinian Museum on the university’s campus titled “Intimate Terrains: Representations of a Disappearing Landscape”.

Among the works that drew my attention in the exhibition was a small corner that showcased a work by the Palestinian artist Yazan alKhalili, titled “On Love and Other Landscapes”. I stood there and flipped through the pages of a photographic book that displayed natural landscapes with a caption written underneath each one:

She took photos of the landscape

She gave me her photos of the landscape

I gave her mine of her[i]

You might wonder, why am I writing about this ‘book’ in particular? What I saw in that work was a meek blend of image and text, a love story narrated by the movement of two people through a series of natural landscapes documented by a camera without showing either of them. As a result, the landscape is the most important witness in the story unfolding on its pages and it is the only thing that finds its way to the pictures, as well as to the list of works that I found closest to me from among those exhibited under the same theme at the exhibition. The camera in alKhalili’s work is a tool that transits the hills, escapes the shadows of the segregation wall. On that particular day, and right before leaving the campus to take the “new” road, alKhalili’s camera seemed to me to be very similar with my sketchbook that was growing and filling with ‘landscape sketches’. Both are capable of freezing time and place, and capturing them in picture frames and sequential drawings; which is what we do when we write a story. We create a sequence of thoughts through photographs and documentary sketches, and allow this sequencing to turn into an artistic work capable of narrating the story of a city, a road or a space; which is a dimension that these works acquire by accumulation over time, and through its connection to a timeline and the seeping in of details such as the weather and the trembling of the bus while sketching a scene or taking a photograph.

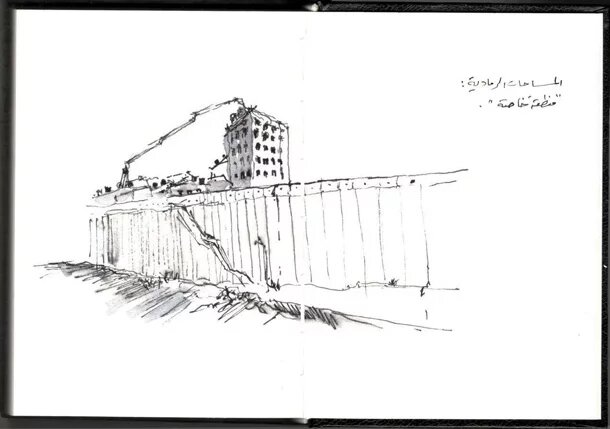

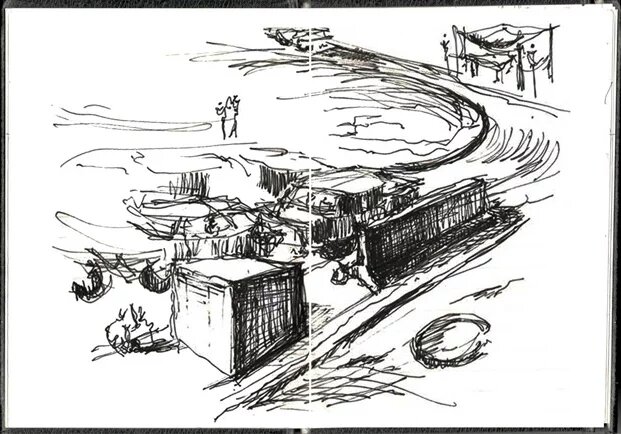

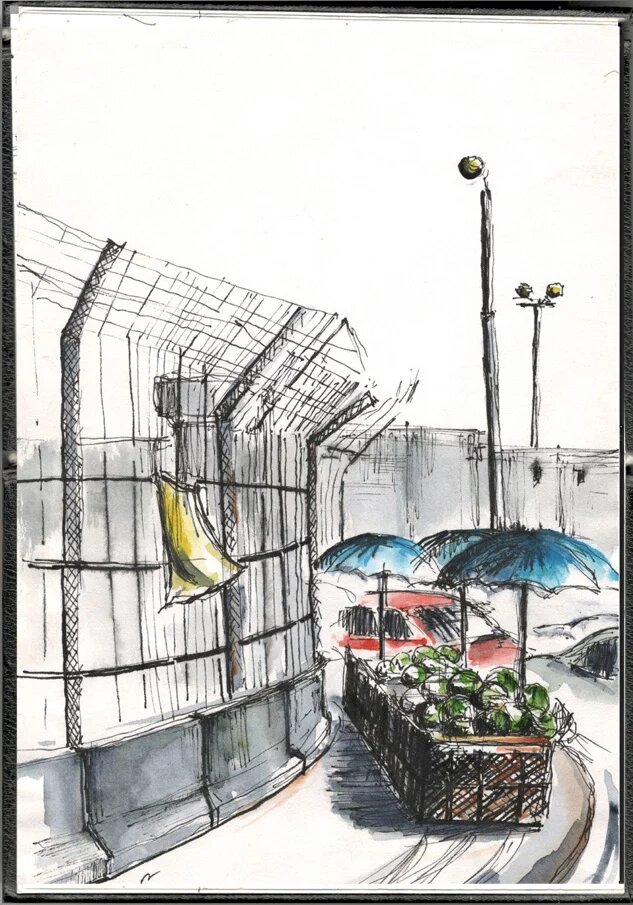

At a time where Yazan’s pictures narrate a story that any of us could be the hero of and to which the natural landscape is a daily witness, our sketches on the roads – as architects, artists or else – tell a similar story; which is what I was observing during my student years without really realizing it: my sketches tell the story of the daily road through Qalandiya through melted lines of graphite, ink and some watercolours that mostly depict the surroundings of the military checkpoint. The checkpoint, located next to the field of the Jerusalem International Airport that was built in the 1920s, is a point that has been ever changing during the last few years. The most important transformation and the most significant in reshaping the area in my eyes was allowing public buses of commuters to cross over what used to be the airport’s runway, which – to me – happened suddenly or in a period that I no longer remember its details today. The open space, which I was not aware existed anywhere in Jerusalem before then, suddenly became part of my visual memory. I do not recollect a clear definition of Qalandiya before it, and I do not hide the fact that it became one of the most impressive (and inspiring) spaces to me: The obscene Hebrew sign “שטח פרטי” or “Private Area” that appears as soon as the bus reaches the runway, the airfield that extends like a cement desert with wild bleak yellowing shrubs on its sides, and its gradual transformation into becoming a bus terminal.

Every time I pass by the checkpoint I still feel like this space has just sprung out escaping a dream. Over the large blue and white markings, where planes were supposed to taxi, the buses operated by the Unified Company pass now on their way to Ramallah, and everyday trails of new constructions appear on what is left of the airport’s field. More rusty steel bars for reinforcements and construction workers pouring concrete and laying down foundations for new erections that I am scared by the mere idea of its coming to being; a literal translation for what is meant by “made it concrete”, i.e. making it real with concrete roots extending into the ground, gradually killing my childhood dream where we have an airport (even if it wasn’t operational) in Jerusalem.

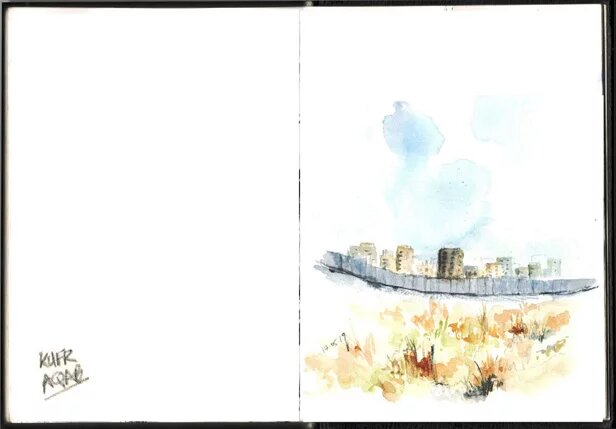

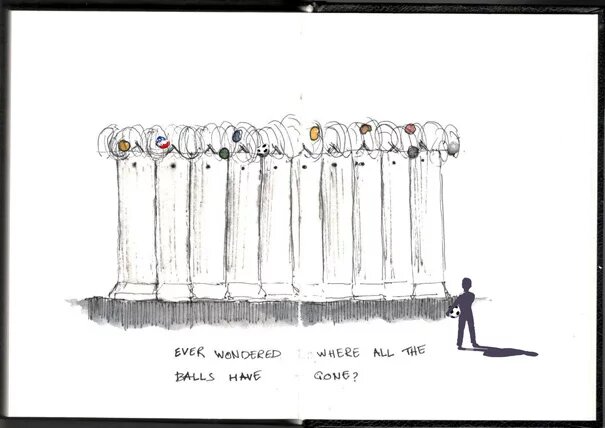

Many of these scenes became a recurrent theme in whatever I draw or think about, and to me passing through the checkpoint was no longer a normal experience (as if it ever could be!). The military space in my sketches materializes through a number of details that made the experience of passing though it even more surreal; like the informal watermelon stand awaiting on the other side of checkpoint, or the 24 rubber balls that I counted once that are trapped in the barbed wire fixed on top of the segregation wall, or the symbolic scene when you stand in the middle of the spacious airfield and turn your eyes around freely until they collide with the segregation wall and Kufur Aqab behind it, that other overcrowded world again. This amazing relay of successive scenes of irony and tensility between spaciousness and overcrowding, and between stability and transformation left no room for the green colour in the picture. Instead it continues to be dominated by the grey of concrete and stone, a picture of fabricated landscapes created by the occupation’s architectural and urban policies that have become part of our simplest and most mundane journeys.

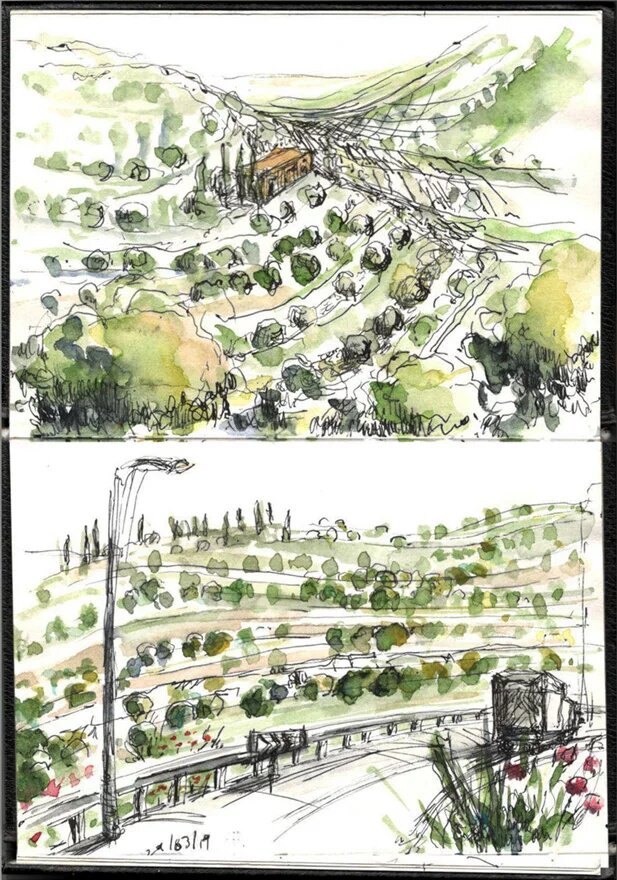

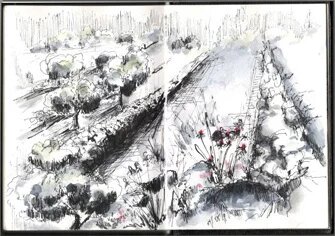

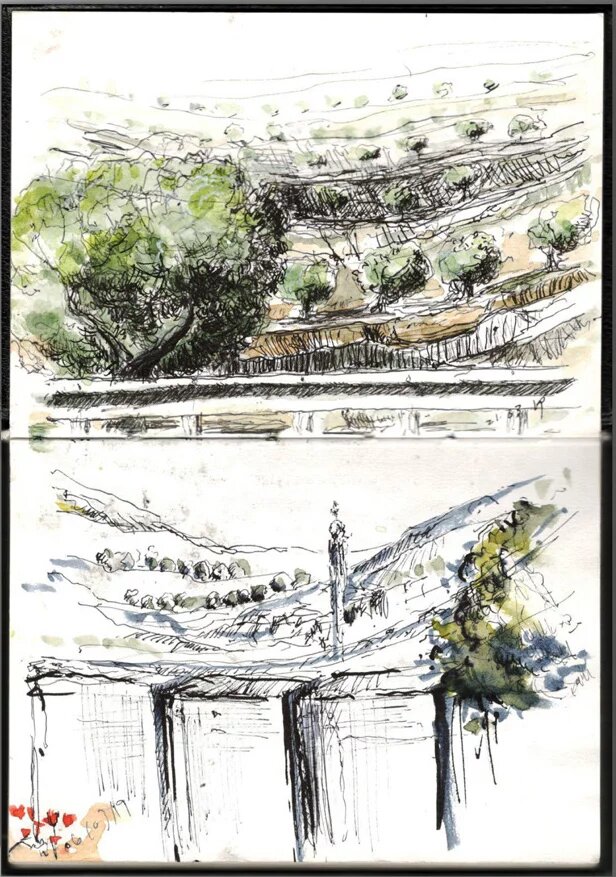

Nevertheless, the green colour managed to find its way back to my sketchbook over the past year as I started commuting through the Hizma Checkpoint. My daily journey now takes me on the roads that cross through the lands of a number of villages that neighbour or overlook Ramallah such as Mikhmas, Silwad and Yabrood; which has allowed me to project some of the romanticism inspired by the hills and open vistas onto my latest sketches.

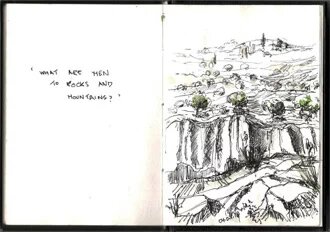

The oppositional experience on these external roads that pass some villages and connect a number of Israeli colonies in the West Bank, is a single window experience. It is a window that opens onto what is left of the authentic Palestinian natural landscape, with its fields, olive trees, and the vernacular agricultural terracings that trace the topographic contours of the stretching hills. The view from the window is a ‘Sarha’ (a space to wander) like the ones that Raja Shihadeh wrote about in the highlands of Ramallah’s villages, and is the lost landscape in many of our grey experiences inside the cities. “Thank God for the blessing of Hizma” is the unusual thought that comes to mind as soon as you realize that you do not have to change vehicles twice to get to your destination, although the winding road is longer than the direct route through Qalandiya, and although it is more susceptible to closures and ad hoc checkpoints.

During this year, this single-line road managed to define the two points I move between as a place of work and a place of residence solely, and transformed my experience of travelling back and forth to an absolute visual one. My feet have not experienced any spot of this road as there are no stops to step out at along the way. Hence I know the road from a distance, I know the shapes of the valleys, the density of olive trees on the hills, the location of a minaret that overlooks one of the villages and a water tower that appears from another, and I use pens and colours to aid me in preserving them. In this new and complex relationship there is something that makes it similar to frequent travelling between places of work and residence, what is historically known as ‘commuting’. This term became popular in urban planning with railways connecting cities, suburbs and other centers.[ii] At a time when developments in modes of transportation still stand as one of the most important factors in reshaping cities and the temporal and spatial relationships between its parts; I find myself drawing a comparison between the a road that connects Jerusalem and Birzeit on one side, and on the other a highway that connects New York with its suburbs. And I wonder whether such a comparison could reveal anything except an abnormality that restricts our ability to maintain an understanding of the concepts of geography and time, and the unnatural development of our Palestinian cities under the undeniable settler colonial reality and its impacts.

My sketchbooks have become my little guide to a landscape memory that I, like many Palestinians, live and pass through. Each of us has her/his medium for preserving our impressions and readings of the transformation of the Palestinian landscape, without having to define the path or the start and end points. But I choose here to do what Yazan alKhalili and Raja Shihadeh did in their works: to think about this repeating exercise in drawing and producing a series of sequential sketches as a proactive process with temporal and geographic dimensions, that is capable of narrating the story of the landscape without falling into the trap of embellishing clichés. This process has transformed over time into a continuous inspection of my visual and spatial memory that form as I commute on two different roads. One is grey with numerous stops, windows and details that provoke the imagination, and the other holds diverse landscapes of open fields that I am starting to classify in my memory as one continuous scene; a scene that I do not always need to look outside the window to capture its details. Instead, I reproduce it anew again in every new sketch, as if the natural landscape that we can only observe through a window has become incapable of changing as powerfully as the urban concrete laden landscape does. In such a context, the otherwise sensitive artistic comprehension of natural landscapes is rendered incapable of seeing daily details and changes, and suffices by reimagining and reproducing the same scene over and over again, using various techniques, as one repetitive scene that abridges an entire stretch of a road.

This personal reading of the various aspects involved in moving between two points is an attempt to write an ever-regenerating memory and a perception that is reshaped by geopolitical changes, day after day. It is at the same time an attempt to reintroduce the Palestinian landscape, with both its natural and urban aspects, as an important factor in forming artistic, literary and geographic awareness; which is the open question that all those involved in arts, literature, urban and architectural practices alike, compete to present answers to, answers that may very much be infinite.

This is an article from the “Takhayal Ramallah” project conducted in 2019 with UR°BANA and Sakiya.