By: Nidal Atallah

Palestinians face many difficulties in solid waste management due to the policies of the occupation, but waste amounts are increasing due to both population growth and consumption patterns. This calls for better management and a concerted effort among all sectors to find solutions to this problem.

Being under Israeli military occupation, for 53 years now, Palestinian governmental bodies are struggling to solve the problem of solid waste. In the West Bank, settlements are encroaching onto Palestinian communities, not only confiscating land and natural resources along the way, but also stripping away Palestinian control and jurisdiction, whatever of it remains anyway. Since the establishment of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA or PA) in 1994, Israel has used the newly established authority as a scapegoat to spare itself the burden of providing the essential services –its duty under international humanitarian law– like collection and disposal of solid waste. At the same time, Israel maintained its absolute control over every aspect of Palestinians’ lives. However, with a growing Palestinian population –now around five million in the West Bank and Gaza Strip–trash has been piling up. This has left the PA scrabbling to find solutions amidst a plethora of complications, restrictions and an overall messy geopolitical situation.

General Overview on Waste

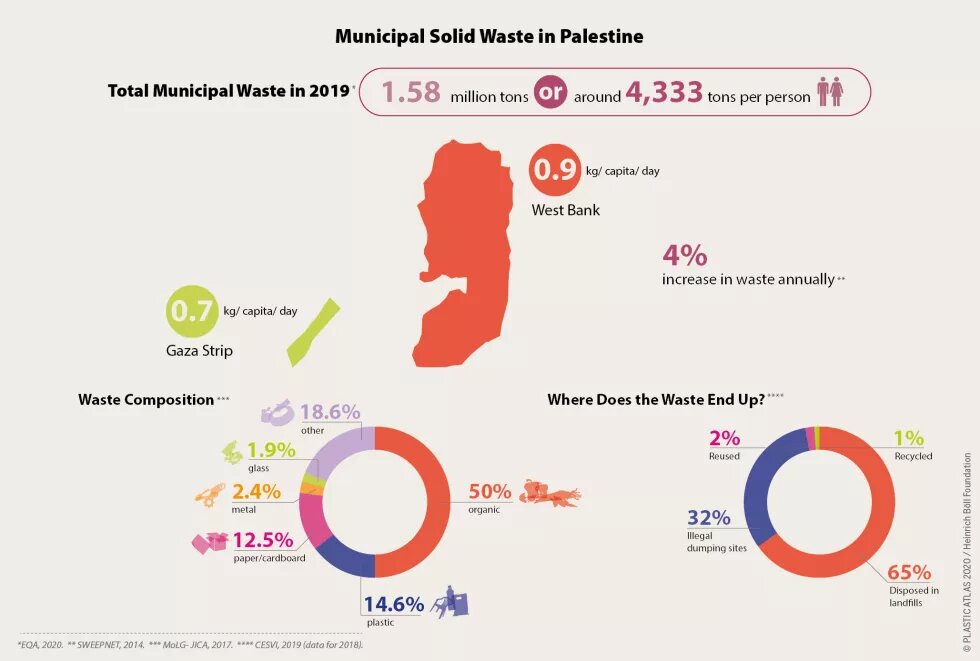

In 2019, Palestinians generated nearly 4,333 tons of solid waste per day or a total of around 1.58 million tons the entire year, which is equivalent to around 0.87 kg/capita/day (0.9 kg/c/d in the West Bank and 0.7 kg/c/d in Gaza). These amounts, which include East Jerusalem, are projected to increase by around 4 percent annually due to both population growth and current consumption patterns. About 65 percent of municipal waste (MW) is disposed in sanitary landfills, while the remaining is disposed in predominantly random/ illegal dumping sites that are a constant source of pollution to the Palestinian environment. Despite the success in managing to close 52 random dumping sites between 2010 and 2016, tens more still exist, taking up hundreds of dunums of land (1 dunum is 1,000 square meters). Add to that the dangerous phenomenon of illegal burning of electronic waste in order to extract raw materials such as metals from wires; an activity that is spreading toxins at alarming rates in many areas, such as Ithna in Hebron.

There are currently five major sanitary landfills in Palestine, three in the West Bank (Jericho Landfill in Jericho, Zahret Al-Finjan in Jenin, Al Menya in Bethlehem), and two in the Gaza Strip (Sofa (Al Fakhari) and Johr Al Deek). Additionally, in 2018, a dumpsite in Beit Anan in the Jerusalem area was turned into an engineered landfill; thought small, it has helped absorbing some of the waste from the surrounding areas as well as from Ramallah and Al-Bireh. The increasing amounts of municipal solid waste is forcing these landfills to function over-capacity and threatening environmental standards on their grounds and on the surrounding environment. If additional ample spaces are not made available, whether by adding cells to the existing landfills or by constructing new ones, they can no longer qualify as being “sanitary”. This is vital especially when considering that the National Strategy for Solid Waste Management in Palestine (NSSWM) 2017—2022 set a target to increase the coverage of sanitary landfills from 53 percent in 2017 to 100 percent by 2022.

Furthermore, the waste arriving from the illegal Israeli settlements exacerbates the already dire situation of these overburdened landfills. Currently, there are over 200 Israeli settlements in the West Bank housing a settler population of more than 620,000. While there are exclusively-Israeli landfills operating in the West Bank, Al Menya Landfill for instance receives waste from the nearby settlements. Additionally, waste from settlements is illegally dumped in numerous random sites, mostly located near Palestinian communities, and with no monitoring or accountability. In September 2016, Afaq Magazine revealed that Israeli toxic organic and non-organic waste is dispersed over thousands of dunums west of the Jordan River and North of Jericho. It also revealed that toxic Israeli compost and contaminated waste is being dumped in open lands near Al-Auja Spring in Jericho, pausing the threat of pollution to the soil and springs in the area. Furthermore, sources of the same magazine indicate that more than half of the electric waste generated in Israel is disposed in the West Bank.

The issue with external sources of waste does not stop here. Israel has been systematically transferring its hazardous waste into the West Bank. In December 2017, the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem revealed the operation of 15 waste treatment facilities in the West Bank. These facilities process hazardous waste and dangerous substances such as medical waste, solvent waste, oil waste, metals, electronics and batteries, as well as sludge. Although the facilities are intended to treat waste, B’tselem says it is still a polluting industry that could have implications on the environment and public health. The report describes Israel’s actions as turning the West Bank into a “sacrifice zone” where Israel’s strict environmental regulations do not apply and where the cost of random disposal is much cheaper, thus allowing Israeli businesses to profit illegally at the account of Palestinians. Palestinian authorities have been trying to challenge the illegal transfer of this hazardous waste through the multitude of international conventions and treaties ratified by the State of Palestine in recent years. Most importantly, they have submitted several complaints and reported numerous violations to the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal.

The Legal Framework between Theory and Practice

At the legislative level, the PA has achieved substantial progress in regulating solid waste management. The most relevant laws are: Local Authorities Law No.1 (1997), Environment Law No.7 (1999) amended in 2013, Public Health Law No.20 (2004), modified Palestinian Basic Law 2005 Article (33), Medical Wastes Management cabinet decision No. 10 (2012), Joint Services Councils (JSCs) Bylaw approved by cabinet (2016), Solid Waste Management cabinet decision No. 3 (2019), and most recently there are two new draft laws expected to be adopted, one on construction and demolition waste and the other on hazardous waste. While issuing these laws along with a number of strategic plans is a step in the right direction, implementation and enforcement on the ground are very weak. National strategies and plans can be characterized as being overambitious, as many of their targets are often not met. Take for instance the target in the National Development Plan (NDP) 2014-2016 to increase the percentage of recycled solid waste to 25 percent by 2016, which according to the NSSWM 2017-2022 made up less than 1 percent in 2017. The latter once again set a new and overly ambitious goal to reach 30 percent by 2022. This indicates a serious problem at the managerial level due to administrative, financial, and technical reasons. Among the financial issues is the inability of service providers to collect service fees, achieve cost recovery, or abandon the dependency on international donor funds.

The aforementioned however, is by no means the only hurdle for the development of the sector. Israel’s permit regime in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt), which extends to all aspects of life including which areas Palestinians are allowed to access or not, remains the main impediment to the implementation and operations of infrastructural projects. All projects in the West Bank have to be approved by the Israeli Civil Administration (CA), which deliberately delays many vital infrastructural projects, and rejects some altogether. For example, Rammun Landfill in the Ramallah and Al-Bireh Governorate was proposed in 2003 with pledged funding from the German Development Bank (KfW). Until today, it has not been implemented yet due to issues with the CA’s approval.

In Gaza, due to the Israeli blockade imposed since 2007, restrictions on the entry of materials have prevented the implementation of vital infrastructural projects, not only in solid waste, but also in water and electrical power. These Israeli policies have persisted despite condemnations by the international community and the heavy involvement of international donors in such projects. The population, over two million, entrapped in Gaza is already suffering from an environmental catastrophe in an area that has been deemed “unlivable”. There must be stronger action by the international community not only to stop the environmental deterioration in Gaza, but also to give the Palestinians justice and their right to self-determination.

The Palestinian Local Authorities Law No.1 (1997) delegates all responsibilities for solid waste management to Local Government Units (LGUs), a reference to local bodies such as municipalities and village councils, under the supervision of the Ministry of Local Governance (MoLG). Their responsibilities include the collection, transportation, sanitary disposal and recycling (if any) of municipal waste. As there were so many of these local bodies, some of which simply are too small and/or with insufficient capacities to take on the responsibility of solid waste management by themselves, many used the option provided in the aforementioned law and merged together to form joint service councils (JSCs). Today, there are 13 JSCs operating in the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and 2 in Gaza. In refugee camps, the situation is a bit different, as the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) is the one responsible of waste collection and transportation. In recent years, UNRWA has faced financial difficulties that led to the temporary stoppage of solid waste services on many occasions, resulting in the unbearable accumulation of waste, evident even to cars driving by the camps.

What About Recycling and Reuse?

Attempts for waste sorting and recycling in Palestine have been marginal. It is estimated that only 1 percent of all solid waste is currently being recycled. In a 2010, around a quarter of recycling in Palestine was that of plastic (Musleh & Khatib, 2010). This percentage is increased to 3 percent when including recovered or reused materials. Nonetheless, there is an exceptional potential for recycling and composting not only to help solve the problem of the increasing amounts of solid waste but also for improving cost recovery and generating new job opportunities. This is especially true when considering that biodegradables and recyclables constitute the majority of solid waste generated in Palestine.

The current recycling and reuse sector in Palestine is relatively small and significantly informal in nature. It includes recycling of glass, plastic and paper/cardboard, hence producing raw materials for local industry but more so for industries in Israel and abroad. The reuse of metal is also taking place, but mostly unaccounted for in the municipal waste stream as it is being diverted through its purchase by travelling trucks that are roaming the streets to collect it from households and institutions. There are some successful examples of waste separation and recycling such as the one in Al Menya Landfill, where some waste materials such as plastic, metal, cardboard and glass are transferred for recycling as well as organic waste that is turned into low quality compost used at the landfill. These types of efforts must however be ramped up to increase the percentage of recycled waste especially that most other current projects are pilot ones and have not achieved the results hoped for at the national level.

As most of the recyclable waste is mixed with other municipal waste, there must be increased efforts for separating waste to encourage further recycling. There are 15 transfer stations in Palestine, receiving about half the waste gathered by JSCs. Recycling policies and the concept of the 3 Rs (reduce, recycle, re-use) are mentioned in official documents, however separation at source is not implemented sufficiently and waste minimization is nearly non-existent. Separation at the household level is needed more than ever in order to avoid the contamination of recyclables when mixed with other municipal waste. However, more importantly, what is needed is a change in consumption patterns arising from the current economic system, and awareness on the need to reduce waste. As has been professed in many parts of this Plastic Atlas, we cannot recycle our way out of the plastic and solid waste problem. Palestinians can actually refer back to the sustainable lifestyle of their ancestors and the rich traditional knowledge and practices that were intrinsically environmentally friendly.

Additionally, organic waste, which makes up around 50 percent of the total municipal waste can be decreased dramatically with simple practices such as composting for gardening at the household level, where possible or on larger scales. Furthermore, plastic is a global problem that is getting worse by the day, and it is contaminating our environment and damaging entire ecosystems. Despite political constraints, Palestine must be part of the global effort to confront the plastic problem. This can only be achieved through a consorted effort by governmental bodies, civil society organizations, and environmental and social activists to raise awareness on the issue at the community level, urging people to refuse the use of plastic in their daily activities, and to reduce waste in general. In parallel, manufacturers and traders must be urged to abandon plastic, moving to more environmentally-friendly materials. They must also be held responsible for their contribution in flooding the market with plastic.

Initiatives

In recent years, awareness on the issue of waste has been on the rise, and many Palestinian community-based initiatives have emerged. Their wide-ranging campaigns and activities have revived the spirit of volunteerism and promoted local-community-supported solutions to big problems. These initiatives are tackling the solid waste issue through different approaches and means, all of which are inspiring. They can be placed in the following categories: volunteer groups leading awareness and cleanup campaigns in both rural and urban areas; initiatives and enterprises on recycling paper/cardboard and plastic, as well as engineers producing building materials from construction waste and the rubbles of destroyed building; individuals or start-ups conducting entrepreneurship projects and creating mobile applications and platforms for material recycling and reuse; artists initiating projects for upcycling of all sorts of materials; individuals and groups raising awareness through blogs and other social media platforms; and finally civil society organizations and community-based groups carrying out awareness campaigns. Additionally, other environmental and agroecology activist groups are also contributing to a discourse that promotes waste reduction and adoption of a more sustainable lifestyle.

These initiatives may be small and may not be able to solve the solid waste problem by themselves, but they give hope for better awareness and a collective consciousness on the issue of waste. We can only wish that their work culminates in a joint effort among all sectors, as well as a stronger political will to address the problem of waste and other environmental issues in Palestine.

References:

- Based on information provided by the Palestinian Environmental Quality Authority, July, 2020.

- SWEEPNET: Country Report on the Solid Waste Management in Occupied Palestinian Territories, April 2014, p.16

- Ministry of Local Government (MoLG)- Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA): Data Book Solid Waste Management of Joint Service Councils West Bank, November 2017. CESVI: Solid Waste Management in the occupied Palestinian Territory, West Bank including East Jerusalem & Gaza, Overview Report, September 2019, p.31.