Plastic, with its different sizes, presents an imminent threat to public health and one that is fatal for terrestrial and marine fauna and flora. The good management of plastic waste, which includes production, marketing, use, collection and recycling, is essentially linked to the economic policy, social aspects, and the environmental measures taken by the country.

Since 1993, Tunisia has set up a national program for solid waste management in order to implement an integrated waste management strategy. Since its creation, the National Agency of Waste Management (ANGeD) started with rehabilitating the unauthorized dumps, establishing controlled dumps, and addressing emitted gas and leachate.

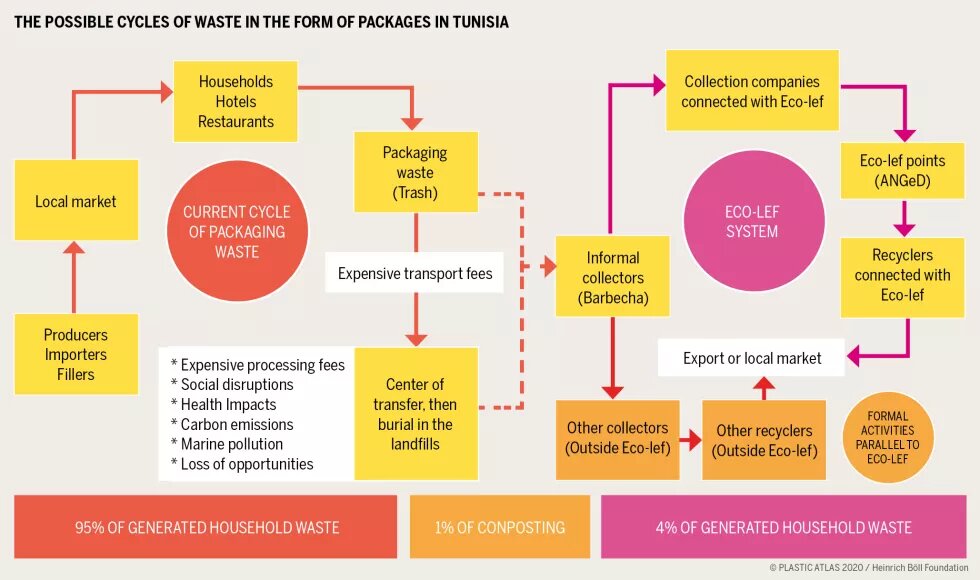

After the Revolution, waste management has been worryingly deteriorating in urban and rural areas, as reflected in the spread of black points due to the disruption in major waste collection operations, the sector’s infrastructure, and the recycling chain. Nowadays, Tunisia produces more than 2.8 million tons of solid waste (9.4 percent of plastic waste), 95 percent of which is buried (according to ANGeD). Currently, the 8 operating landfills are coming to the end of their life and require alternative solutions that highlight waste recovery. The ANGeD currently manages a public system entitled “Eco-lef” which stands for the recovery and the diversion of used packages, in accordance with the provisions of decree no. 97-1102 dated 2 June 1997 laying down the conditions of recovery and management of packaging bags and used packages as modified by decree no. 2001-843 dated 10 April 2001.

On a practical level, the system encourages the private sector to collect packaging waste through establishing micro- enterprises specialized in collecting and selling the collected products to ANGeD. Most of the quantities are collected from households or landfills by rag pickers, known as “Barbecha”. The agency ensures thereafter an equal distribution of these quantities to approved recyclers licensed by the system at a subsidized price. The selling conditions and prices are stipulated in an agreement related to collection and recycling, between both parties, namely ANGeD and the concerned company. Depending on the polymer type (i.e. plastic), 70 to 90 percent of the collected plastic waste is recovered. In the activity of recycling plastic materials, PET (transparent and flexible bottles) is generally collected, washed, and crushed on the spot and exported mainly to Turkey and some other countries such as Vietnam. As for PEHD (opaque caps and bottles), it is collected, washed, crushed, and transformed into raw materials in Tunisia.

WHAT DOES ECO-LEF MEAN ?

“ECO” stands for ecology, and “Lef” for packaging. It is a public system pertaining to the recovery of used packages, which came into being in 1998 following the application of the provisions of decree no. 97-1102 dated 2 June 1997.

WHY WAS THE ECO-LEF SYSTEM CREATED?

The ECO-Lef was created in order to:

* Reduce the landfilling of packaging waste

* Limit the negative impact resulting from leaving packaging waste in nature

* Promote recycling and packaging waste recovery

Notwithstanding the big principles laid down in the law, there is currently no clear strategy in terms of sector development and no objectives regarding the results or the recovery rate to be achieved.

Created in 2001, Eco-lef is the first system for the management of packages in the MENA region and among the firsts in Africa. The system was built on a solid legal and an institutional basis. Today, and after twenty-three years of its activation, there is no doubt that it has contributed to the creation of a new first-order economic, social, and environmental sector. Nevertheless and despite all achievements and efforts, the performance and the governance of the current system is still very limited. In fact, very small quantities are collected compared to the massive quantity of plastic that continue to invade our environment at a stunning speed.

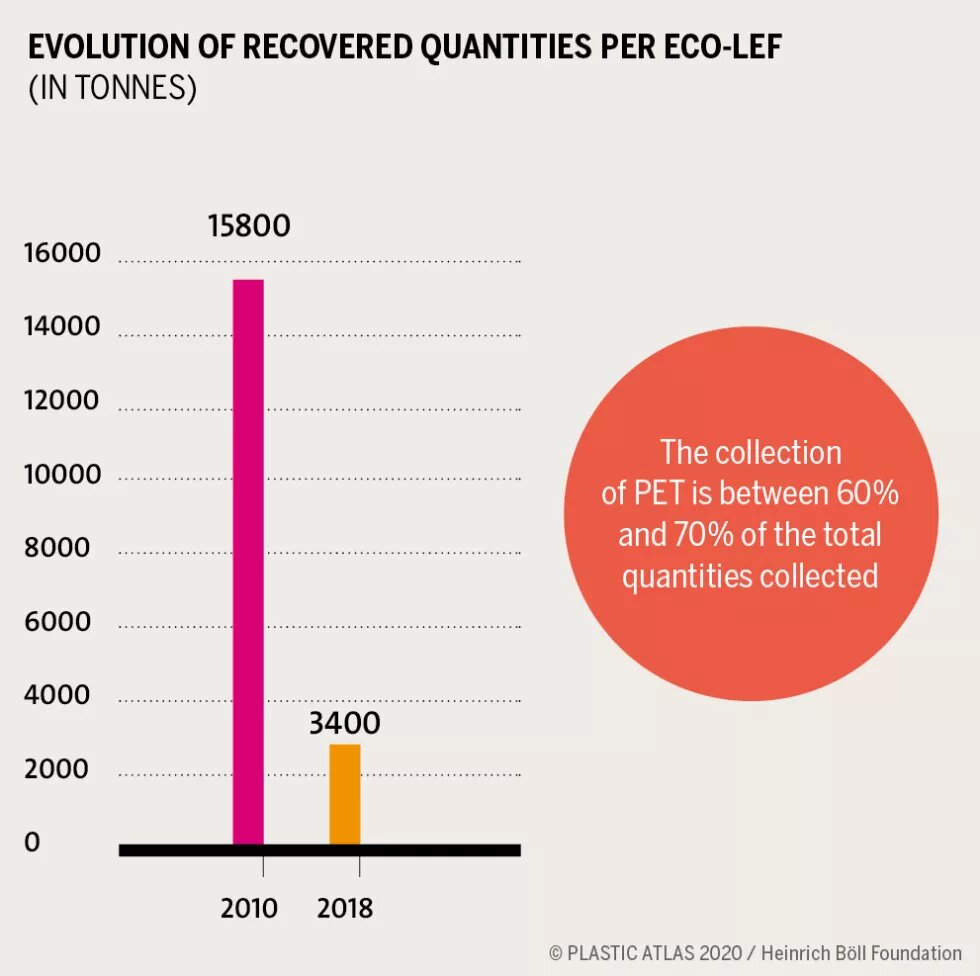

The Eco-lef system faces many challenges that are manifested not only by the decrease of collected quantities, but also by the decrease in the number of active recyclers and Eco-lef members. Today, there are only 70 institutions that are really active. The same applies to the number of Eco-lef collection points, which dropped from 63 points in 2010 to only 45 in 2018.

Obviously, the collapse did not spare the active collectors and Eco-lef members. In fact, only 180 remain according to 2018 calculations, whereas 230 were active in 2010.

Currently, the Eco-lef system is funded by voluntary contributions of some producers and by the support of the decontamination fund (FODEP) through a tax of 5 percent on turnover charged to importers and producers (funding based on the collected quantities and activities of each year). It is also worth noting that contracted producers of packages, in other words those with contracts with the agency, are not required to pay a specific amount since it is regarded as a voluntary contribution, especially in the absence of means of control. In addition, the payment is not flexible enough according to the needs of collectors and recyclers and the price of materials.

The organizational difficulties are mainly caused by the absence of selective sorting where the waste is produced. Even worse, the 8,000 informal collectors or “Barbecha” are not officially involved in the system, according to the ANGeD report, despite the key role they play by collecting 80 percent of recyclable waste.

In the same context, we notice that the consumer is not involved and therefore does not bear any responsibility.

Furthermore, the collection activity within the Eco-lef framework is related only to valuable materials (positive price on the market) such as beverage bottles type PET, PEHD, etc. However, the other types of packages are still not collected because of the absence of an appropriate infrastructure. Moreover, no incentive for innovation or for developing the recycling industry has been made in Tunisia. A large number of Eco-lef points have experienced equipment degradation, while other centers were taken over by the concerned municipalities without suggesting any alternatives.

In light of the current situation in Tunisia, we do not sense the absence of an overview of what is collected and of precise and reliable data of the packages placed on the Tunisian market. The private sector is also active outside Eco-lef. It is prospecting new collection circuits and seeking to develop the plastic recycling and recovery. These activities are legal but represent a competition for the system. Unfortunately, there are no exact figures about collected plastic quantities by the private sector.

The Eco-lef sector needs to be refreshed and optimized to keep up with the new systems of extended producer responsibility (EPR) applied in developed countries. Under the EPR, manufacturers and distributors of trademarks, and importers who put waste-generating products on the market, should take charge of the organization and the funding of their packaging waste through an ecological system. Likewise, the EPR represents a chance for the market of collection and recycling in Tunisia as well as for the waste prevention at source through the improvement of the packaging design to make more recyclable products. The system will support municipal efforts in terms of waste management and will considerably reduce the costs of collection and treatment.

On a global scale, it has become very frequent that cities make strict decisions regarding single-use plastic. In Tunisia, the decentralization framework should start a real battle conducted by municipalities against plastic. In fact, the local authority can launch participative initiatives to reduce, sort, and recover plastic waste. It can even start to ban a few types of plastic by planning suitable programs and aim for longterm change.

This is a chapter from the Plastic Atlas 2020.