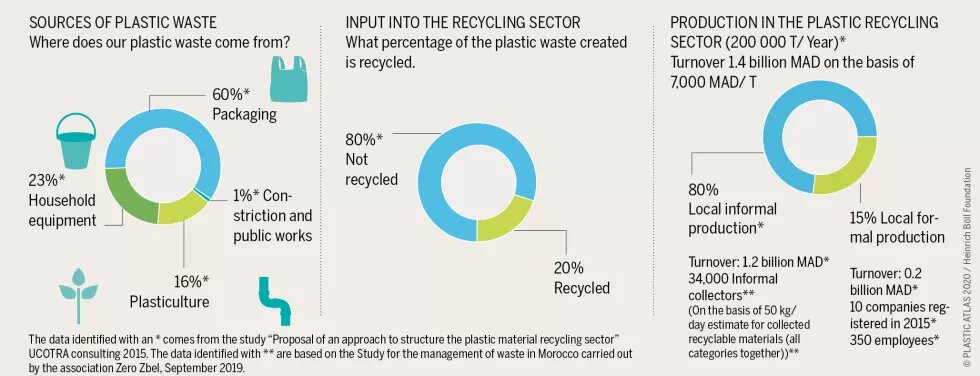

Plastic represents 10 percent of household waste in Morocco or around 690,000 tonnes a year. There is also a lot of plastic found in industrial waste (granules, industrial packaging waste...) and in waste produced by the agricultural sector. Yet, only a very small portion of this is recycled.

Plastic waste of all sorts is the most visible form of waste in the countryside and nature in Morocco. Investigations carried out by the association Zero Zbel on beaches, mountains, and in the desert, on over 50,000 pieces of collected and categorized waste, showed that plastic waste is systematically the most common form of waste (on average 74 percent).

The plastic recycling sector in Morocco has a very limited number of formal actors (10 companies identified in 2015) that have been organized into professional associations and federations. There are, however, a multitude of informal actors who represent the vast majority of the industry (up to 85 percent of the turnover according to certain studies).

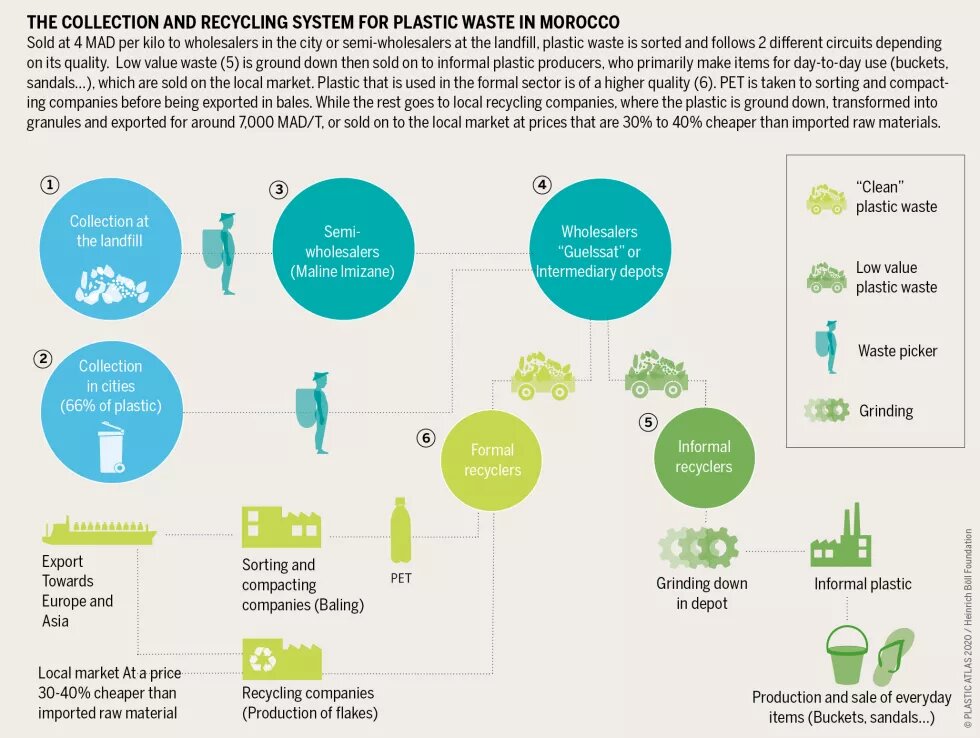

34 percent of plastic that gets sorted comes from landfills and 66 percent comes from cities, recovered at the level of household waste collection points by informal waste pickers, pejoratively called “Mikhala” or “Bou’ara.” These men and women represent a fundamental pillar in the recycling sector since they are the only ones to enable the constant sorting of plastic waste needed to supply the industry. Yet, their working conditions are often incredibly harsh and unstable. Official figures estimate the number of informal waste pickers in Morocco to be between 7,000 and 10,000. According to estimates by the Zero Zbel Association, based on a calculation of the quantities recovered in the informal sector, there may be as many as 34,000. Several initiatives already aim to help organize these people into cooperatives to do the sorting work at the landfill, but those working in towns and cities have not been involved. Officially, twenty informal waste picker cooperatives exist, but even the most successful experience amongst them ends up sorting only 2 percent of the waste sent to the landfill where they work. Essentially, this is due to the time the waste spends in transfer centers, which reduces the quality of the recovered plastic, making it less viable for recycling. What is more, the lack of waste pickers’ collectives makes it difficult to create a viable economic sector. The absence of organized plastic sorting systems at the source leads to plastic waste being dirtier in general, contaminated by leachate, fats, etc.

As a result the quality of the plastic is lower and recycling becomes more costly.

60 percent of plastic recovered for recycling comes from the packaging sector (bottles, tubs, caps, etc.). After sorting and collection by informal waste pickers, the waste is sold to semi-wholesalers, or directly to wholesalers in “guelssas” (intermediary depots) located in the city. The recyclable plastic material is then sold on to formal companies and, for the most part, exported abroad (France, Spain, Italy, Turkey, Asia...). A small part is recycled in Morocco, often at an uncompetitive price.

Given the difficulty of acquiring quality recyclable material (uncontaminated), the central role played by the informal circuit and the proven inefficiencies in sorting plastic waste, it becomes clear that reducing the dumping of waste and promoting the sorting of waste are the best means of significantly improving waste management in general and reducing plastic pollution in particular.

Efficient initiatives linking the decentralization of waste management and the integration of informal waste pickers already exist in many large cities of the global south (e.g. Manila, Bogotá, Buenos Aires...). These decentralized systems cost a lot less and are more efficient in creating jobs than systems based on sending waste to landfills and sorting afterwards. The city of San Fernando in the region of Manila in the Philippines made the decision to create small sorting centers by neighborhood and to employ former informal waste pickers to collect and sort. The cost of managing household waste was reduced by 70 percent, as 80 percent of waste was sorted for recycling. Only 20 percent ended up being buried in landfills.

In Morocco, it is essential to put in place a system that enables the sorting of waste at the source. On the one hand, officially authorizing informal waste pickers to recover recyclable waste in urban areas would enable their integrate into the recycling economy (formal system), to improve sanitary, environmental and economic conditions for their activities and to supply recycling factories with clean and cheap raw materials to transform. On the other hand, involving households would help people better understand and participate in transforming the relationship we have with waste.

In any case, prevention is better than cure. This means that it is essential and necessary to employ measures to reduce plastic waste early on to avoid pollution afterwards. In financial terms, preventing plastic pollution would be decidedly cheaper than trying to mitigate its ensuing external negative effects.

This way, legislators as well as citizens have a major role to play in order to encourage producers and distributors to sell their products without single-use packaging (in bulk or through reusable packaging), to effectively eliminate bags and disposable plastic products, promoting systems of refundable containers or any other viable and sustainable alternatives.

The government is also responsible. The existing eco-tax on factory production, sale, and import of plastic materials, which came into force in 2014 with a fixed rate of 1 percent ad valorem in the 2016 budget, must be reviewed and its funds used in a way that leads to a tangible impact on reducing plastic pollution. Creating systems of broader responsibility for producers is also needed to promote the design of environmentally friendly products for Moroccan consumers. This means that the state must encourage producers, though tax advantages and a regulatory framework establishing specific responsibilities, to choose to create “greener” consumable products, all while promoting alternatives such as refundable packaging systems, bulk selling of products and family offers.

Today, it goes without saying that the collection-sorting- recycling sector in Morocco is dominated by the informal sector, which accounts for about 90 percent. This sector provides 34,000 low-skilled and often illiterate workers with a means of living and opportunities for personal and professional development. Nevertheless, the sector harbors many uncertainties which do not encourage extensive investment. The lack of professionalization penalizes the competitiveness of the entire Moroccan plastic sector on the international market. The reasons that hinder the development of this sector are many, and they can only be fully engaged with through multi-party contributions and a national debate including all the relevant stakeholders.

This is a chapter from the Plastic Atlas 2020.

References:

- Study on waste management in Morocco by Zero Zbel, September 2019

- Waste audits carried out in Morocco by Zero Zbel, Spiralium, Association Horizons and Surfrider Foundation

- Data from: ”Proposition d’approche pour structurer la filière recyclage des matières plastiques”, UCOTRA Consulting, 2015