Four years after the ban on plastic bags in Morocco, one can notice that they are still used extensively. Efforts have been put into action to formalise this ban, but some of the approaches adopted since the law 77-15 was passed have had limited effects.

Morocco has created the image of being a country strongly committed to sustainable development, thanks to investment in renewable sources of energy and the organisation of the COP22 in 2016. Similarly, Morocco has also adopted a law to fight against plastic pollution. Beginning on 1 July 2016, the 77-15 law (commonly known as the Zero Mika Law) banned the production, import, sale or distribution of single-use plastic bags. Since then, the reality on the ground has shown that more than just a law is required to get rid of plastic bags. This is not surprising in a country that had the second highest per capita consumption of plastic bags in 2015.

Just before the Zero Mika law came into force, the communiqués from the Ministry for Industry stated that there were 26 billion plastic bags consumed each year in Morocco, or 800 bags per inhabitant. Plastic bags were used, and are still used, for a myriad of different purposes: to buy vegetables, buttermilk “lben”, 200g of olives, as rubbish bin liners or even to cover old TV antennas since, apparently, it helps to better capture signal. It is in this context that the 77-15 law was passed in December 2015 with the total ban on plastic bags coming into force just 7 months later on the 1 July 2016. The passing of this law was met with strong resistance from the plastic industry and disbelief on the part of citizens who saw in this ban just another constraint to their day-to-day lives. Other countries, especially in Europe, have established less restrictive laws that announced the arrival of similar bans two years ahead of schedule in order to prepare public opinion and allow for a smooth transition for the industry.

A national communication campaign that lasted a month and a half was launched in June 2016 just a few weeks before the ban. The new law was also accompanied by a national campaign to collect plastic bags, organised by the Moroccan Coalition for Climate Justice (CMJC), a group of 150 NGOs that had the authorities’ support. The majority of the bags collected were burned in cement factories or disposed in landfills. Until the end of 2016, the press reported on checks made on markets by authorities and the seizing of illegal stockpiles. Morocco was celebrated for its efforts, and visitors to the COP22 appreciated the cleanliness of its cities and countryside. In January 2017, the Ministry of Industry drew up a positive assessment stating that “since the coming into force of the law, the use of plastic bags has considerably been reduced: it has almost been eradicated from modern shops and the use of alternative products has seen an increase in smaller local shops.”

At the same time as this ban, several alternatives were promoted. A support fund for the reconversion of companies was subsidised, to a maximum of 75.5 million MAD, so that they could produce paper bags, as well as woven and non-woven bags. These alternatives were called “environmentally friendly,” despite the majority of them being made out of plastic. Non-woven bags are made of 100 percent plastic, using a polypropylene fabric, and are often called “fabric bags.” Initially, they were sold by shopkeepers, but faced with customer dissatisfaction they are now given free of charge and have become just as disposable as the previous bags. More than three billion non-woven bags are produced in Morocco every year. 40 percent of financing from the support fund for the reconversion of companies went to non-woven bags and their production has increased by 56 percent since 2016.

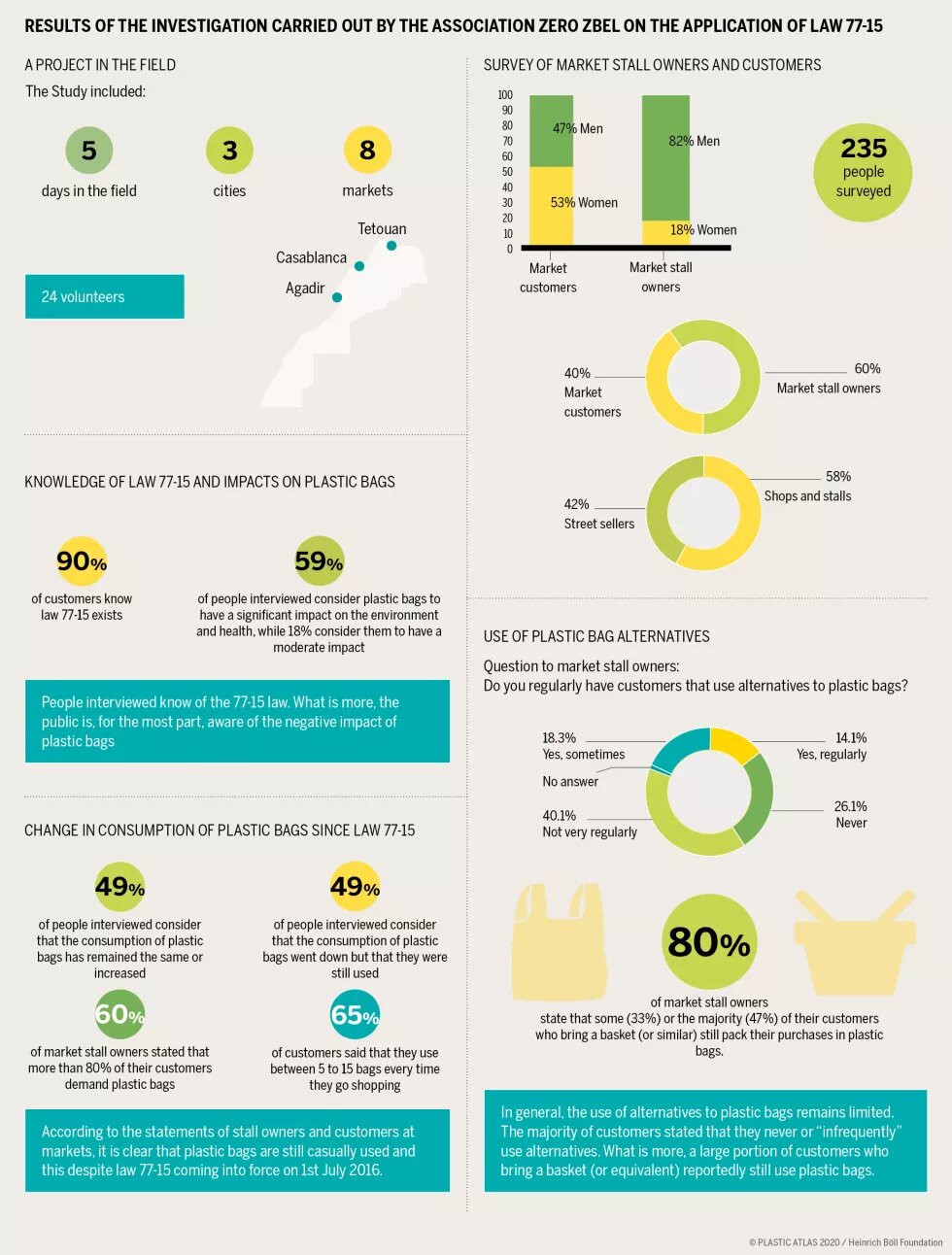

In reality, the ban on plastic bags has had a particular effect on large supermarkets. However, since the start of 2017, plastic bags have progressively reappeared on markets and in small shops, which represent 80 percent of retail outlets in Morocco. In July 2018, on the second anniversary of the Zero Mika law, an investigation was carried out by the Zero Zbel Association and confirmed this idea. Carried out in 10 markets in Casablanca, Agadir and Tetouan, this investigation showed that customers on the markets still consumed large quantities of illegal plastic bags and that stall owners preferred to risk a fine than to risk losing their clientele if they didn’t distribute plastic bags anymore. The main conclusion of this investigation was that efforts to check and punish must be concentrated on the informal sector producing plastic bags, which once again can be found everywhere in Moroccan markets, and not small shops that are at the end of the value chain.

In the days that followed the publication of the investigation results, the Ministry of Industry reacted positively and announced an amendment to the 77-15 law, which was adopted by the government in January 2019 (draft law 57-18). This amendment strengthened checks on manufacturers, targeted transparency on the import of raw materials that would be used to produce plastic bags and raised the amount of possible fines.

Despite these measures, plastic bags remain. This is clearly shown in the rush to purchase plastic bags that preceded the coming into force of the ban and continues to limit the efficiency of the law. More participative decision-making, longer preparation times and a more significant effort to prepare citizens would surely have enabled the ban to be more efficient. The choice of promoting polypropylene alternatives also strongly limits the potential of reducing plastic pollution, which remains present in all its different forms. Real alternatives are there and are not costly, whether be it wicker baskets, fabric bags, reusable rigid containers, or glass jars. It would be good to promote the use of effective and creative alternatives instead of continuing to subsidise alternatives that are, for the most part, still made out of plastic.

This is a chapter from the Plastic Atlas 2020.

References:

Ministry of Industry, Trade and Commerce of the Green and Digital Economy, “Ban of Plastic Bags: Positive Results Six Months after The Law Entered into Force” https:// bit.ly/30YCR7W

Ministry of Industry, Trade and Commerce of the Green and Digital Economy, “Interdiction des sacs en plastique”, https://bit.ly/30yvqe1

Mapecology, “L’interdiction des sacs en plastique : la loi 77.15, un pas décisif ”, 03.01.2019, https:// bit.ly/2OvoMrV

Zero Zbel, Mamoun Ghallab, “PRESS RELEASE JUNE 29TH 2018 On the occasion of the 2nd anniversary of the law banning plastic bags in Morocco Publication of survey results on the use of plastic bags and their alternatives in Morocco” https://bit.ly/3h14WRH