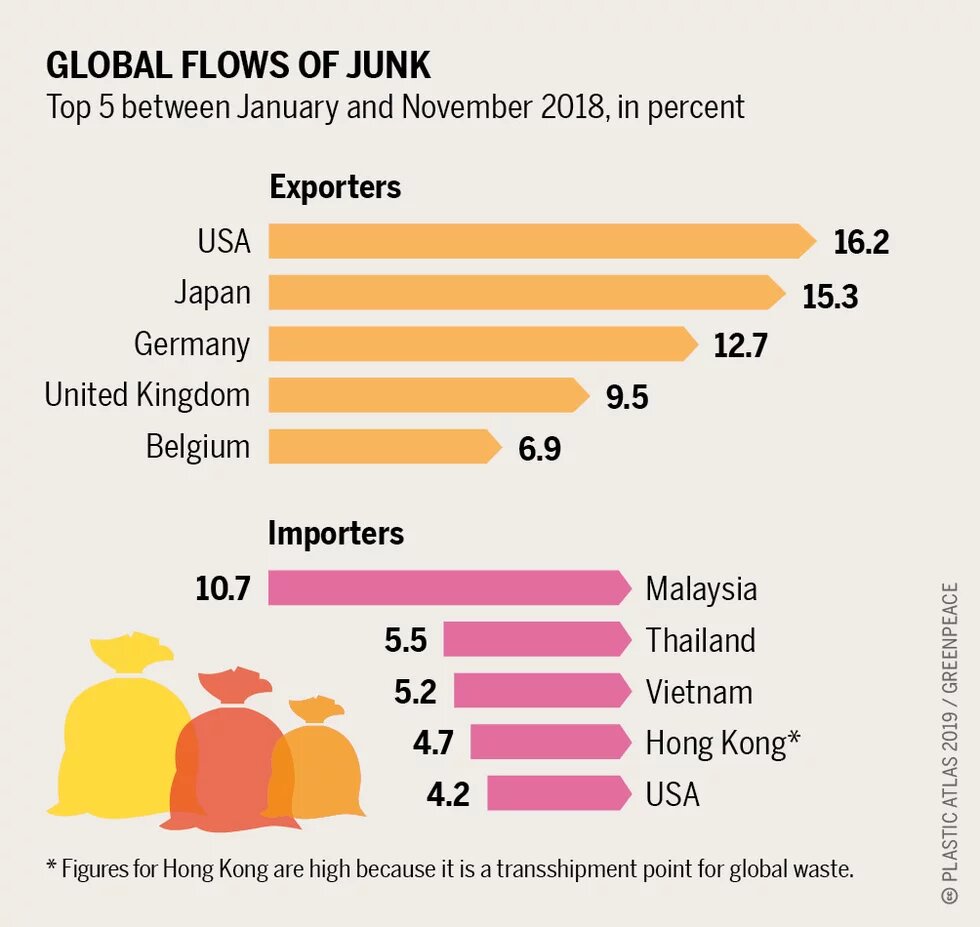

What to do with your unwanted plastic bottles and bags? Simple: send them somewhere else. Until recently, much of the developed world’s hard-to-recycle waste was shipped off to China. That is no longer an option.

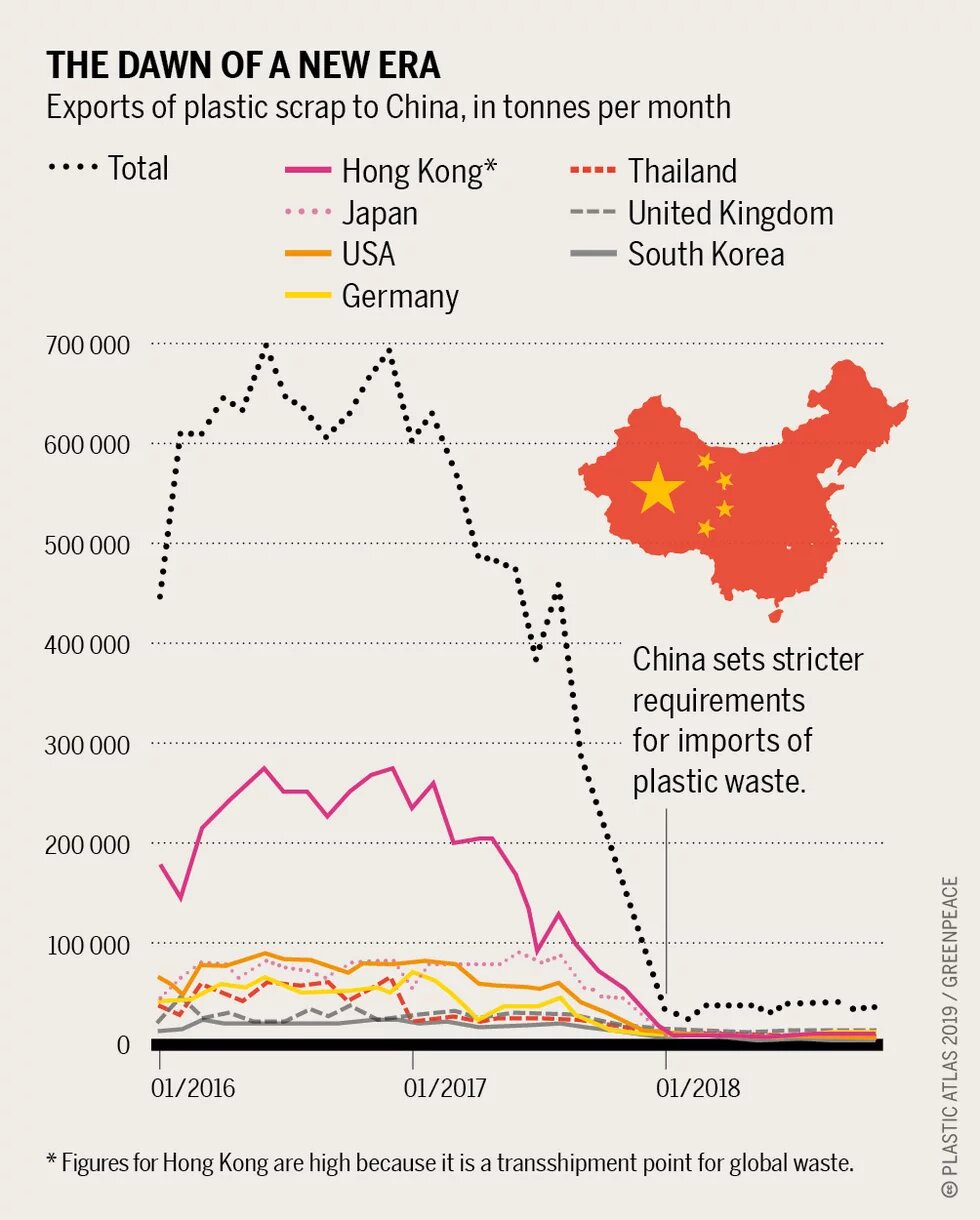

Until January 2018, China was the main destination where exporting countries (predominantly G7 nations) sent their plastic waste to be recycled. Since 1988, around half the planet’s plastic waste has been sent to this country to be melted down and turned into pellets. That changed dramatically when China announced it would only accept bales of plastic waste with less than 0.5 percent contamination by non-recyclable materials - a much higher bar than the previous level of 1.5 percent. The new standard is almost impossible to meet, given that plastic material entering recycling facilities in the United States may contain 15 – 25 percent contamination. The new rule effectively banned the vast majority of plastic scrap imports and created a moment of reckoning for international recycling markets.

China had many reasons for shutting its doors to foreign waste. “Materials recovery facilities” in the developed world would sift through plastic waste, sort out the valuable stuff (like PET and HDPE) for recycling locally, and ship the remaining low-quality items off to China. Such waste contains a variety of materials, chemical additives and dyes that make it next to impossible to recycle. Workers who process these shipments are often exposed to hazardous chemicals. The plastic that cannot be recycled is disposed of in incinerators, landfills or dumpsites, polluting the air, land and sea. These environmental and social ills led China to close its borders, drastically shifting worldwide flows of plastic waste.

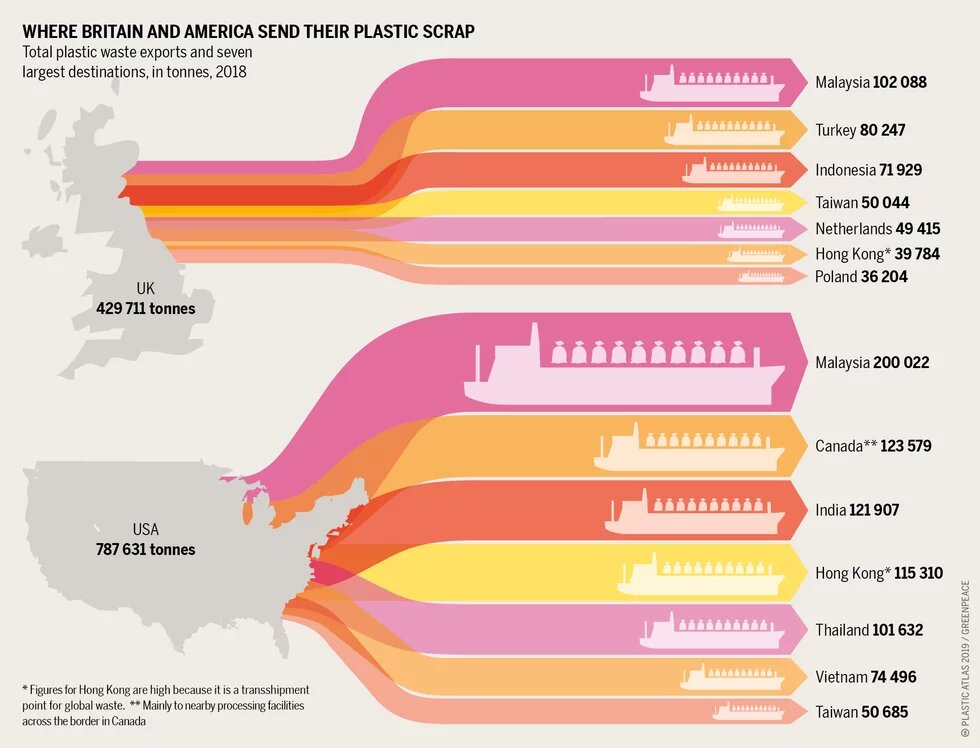

With the primary importer of plastic waste out of the market, exporting countries began sending increasing volumes of scrap to Southeast Asia. In Thailand, imports of plastic scrap rose nearly seventy-fold in the first four months of 2018 compared to the same period in 2017, and in Malaysia they rose over six-fold. In the same time period, imports in China fell by 90 percent. The sheer quantity of imported scrap overwhelmed ports and caused a sharp uptick in illegal recycling operations and waste shipments. In May 2018, a big Vietnamese shipping terminal temporarily stopped accepting scrap materials after it had amassed more than 8,000 containers full of plastic and paper. In Malaysia, almost 40 illegal recycling factories were set up, dumping toxic wastewater into waterways and polluting the air with fumes from burning plastic. In just a single raid, inspectors in Thailand found 58 tonnes of illegally imported plastic.

The environmental and human health impacts have led many importing countries to restrict or ban imports of plastic scrap. In 2018, both Thailand and Malaysia announced bans on imports of plastic scrap by 2021; in 2019 India and Vietnam followed suit with their own plastic import bans. Indonesia has restricted imports of non-recyclable waste.

These countries are also cracking down on contaminated foreign waste imports — by sending them back where they came from. In May 2019, the Philippines succeeded in getting Canada to take back the waste that had been mislabeled and dumped there six years previously. That same month, the Malaysian Minister of the Environment, Yeo Bee Yin, said her country would by the end of the year ship back a total of 3,000 tonnes of waste, or around 50 containersful, to countries like the UK and USA.

In July 2019, Indonesia announced it would return 49 containers at Batam port to Australia, France, Germany, Hong Kong and the USA because their contents violated laws on the import of hazardous and toxic waste. That same month, Cambodia declared it was “not a dustbin” for foreign waste, and would be sending back 1,600 tonnes of garbage.

Facing mounting piles of post-consumer plastic and a collapsing global recycling market, exporting countries have resorted to landfilling or burning recyclables. In the UK, thousands of tonnes of mixed plastics collected for recycling are being sent to incinerators. In the USA, cities in Florida, Pennsylvania and Connecticut incinerate their recyclables; other municipalities across the USA landfill materials they cannot stockpile. Australia has announced that exports of recyclable waste would be banned to prevent ocean pollution, and is considering incinerating its plastic waste.

But incineration emits carbon monoxide, nitrous oxide, particulate matter, dioxins, furans, and other pollutants linked to cancer, respiratory illness, nervous disorders and birth defects. Such emissions threaten nearby communities. The residual ash may end up contaminating land and water.

Asia’s bans and restrictions and the mounting urgency of the plastic waste problem have led to suggestions for reforms to the global waste trade system. In May 2019, 187 countries agreed to amend the Basel Convention (which governs trade in hazardous wastes) to subject shipments of scrap plastic to tighter controls and greater transparency. Set to come into effect in 2021, this amendment will create more accountability around the plastic scrap trade, preventing its worst effects and paving the way for more substantial reforms.

![]()

While the world struggles to handle the flood of waste, industry plans to increase plastic production by 40 percent in the next decade. The rising costs of plastic waste are forcing governments to take action. Cities and countries are imposing bans, fees and other restrictions on single-use packaging in an effort to force producers to change their business practices. The world is starting to understand that we cannot recycle our way out of plastic pollution: we simply need to make less of it.

This is a chapter from the Plastic Atlas 2020.