Produced by: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung – Palestine and Jordan as part of the Online Dossier “Clean it Up: Waste in the Middle East and Northern Africa – new ideas how to deal with it”, 2018.

Article by: Mohammad S. Al-Tawaha and Clara Geiger

The Red Sea is unique! A narrow and deep strip of water stretching around 2000 km between the Sinai Peninsula in the north and the Gulf of Aden in the south, it divides the continents of Asia and Africa. Connected to the Mediterranean Sea via the Suez Canal it is one of the most heavily used waterways in the world. At the same time, it contains distinctive coastal and marine environments and is considered one of the richest and most diverse ecosystems in the world. The Red Sea has the highest levels of hard corals (Scleractinian) in the Indian Ocean region and more than 1,280 fish species. According to scientific references, the Red Sea has the highest levels of endemic marine organisms, as 12.9% of shallow fish species and 19 out of 346 species of hard coral species (5.5%) are only found in the Red Sea.

They attract scuba divers and snorkelers from all over the world who flock to the most spectacular spots in Sharm el Sheikh and Dahab on the Sinai Peninsula and Hurghada on the eastern coast of Southern Egypt. The crystal clear water offers them a glimpse onto the unique beauty of the coral reefs with all its diversity of colours and species.

Coral reefs are not only beautiful; they are also significant ecosystems on a global scale. Coral reefs host an amazing amount of marine biodiversity and assist in water calcification, protect coastlines by reducing wave action and consequently prevent coastal flooding, minimizing the effects of storm damage, ocean acidification, and beach erosion. Moreover, they provide valuable resources such as materials for construction, pharmaceutical and biochemical industries and generate income for the people who live on the shore through fishing and tourism.

Despite the fact that coral reefs have been existing and surviving for millions of years, today they are considered one of the most fragile marine ecosystems under direct threat by human activities. A prime example on this threat is the Great Barrier Reef stretching over 2,500 kilometers along the eastern coast of Australia, which is facing a sharp decline of coral reefs over the past decade and experts warn that it could be exterminated all together unless serious efforts are made to protect it.

The situation in the Red Sea is similar. The coral reef systems are threatened by climate change, pollution, industrial use and tourism. This can be observed in the waters of the southern Jordanian city of Aqaba.

This ancient town that today is home to around 150,000 inhabitants and one of Jordan’s fastest growing cities, and its only outlet to the ocean and thus to the world. It provides the desert kingdom with its only port through which most imports and exports go through. It also offers 27 kilometers of beaches that attract tens of thousands of domestic and foreign visitors each weekend and during the vacation months. The coral reefs along the shores of Aqaba are more than 6,000 years old and include rare and beautiful species. They can be explored at 21 diving locations along 13 kilometers of coastline stretching all the way to the border of Saudi Arabia. 250 out of Aqaba’s 516 fish species inhabit these reefs, says Ehab Eid, Director of the Royal Marine Conservation Society (JREDS) that is a long-time partner of hbs Palestine & Jordan. In 2016, the organization issued the region’s first guide on toxic creatures present in the Gulf of Aqaba. It also promotes the efforts to list the coral reefs in the Gulf of Aqaba as a UNESCO world heritage site.

Due to the rapid growth of Aqaba and the ongoing privatization of its beaches, the diving sites and the reefs are under threat and Jordan is exploring new ways how to safeguard the corals and attract tourists at the same time. In 2012, marine scientists relocated corals from two of the southernmost diving sites to the new Aqaba marine park that opened to the public in 2018 in order to replenish and revive coral reefs that diminished over the course of the last decades. According to Nedal Al-Ouran, head of the Environment, Climate Change and DRR (Disaster Risk Reduction) Portfolio at the UNDP and one of the scientists behind the coral relocation, the replanted corals have not only survived but grown up to 5 centimeters per year.

Moreover, to attract not only divers but also fish and corals, sunken wrecks are used to become tourist attractions and to provide an anchor for corals to settle on. In Aqaba, two sunken ships, a sunken tank and since 2017, even a sunken plane are turning into artificial reefs. The oldest wreck, the ship “Cedar Pride”, was submerged in 1985 and today is encrusted with corals and surrounded by fish.

Although the corals in the gulf of Aqaba have shown remarkable resilience they are threatened by climate change, pollution and littering.

Marine Litter - A Global Problem

Marine litter is among the most serious global man-made problems that negatively affects marine environments and threatens organisms. The countries surrounding the Red Sea are no exception and experience this issue every day. Marine Litter includes any human-made, manufactured or processed solid waste material that enters the marine environment, originating from various locations and sources, both land- and ocean-based. Marine litter can travel over long distances before being deposited onto shorelines or settling on the bottom of the oceans and seas.

Ocean-based litter can originate from fishing activities, boats and ships, offshore drilling rigs and other sources (UNEP, 2019).

Up to 80% of marine litter worldwide originates from land-based sources (PERSGA/UNEP, 2008; Mehlhart and Blepp, 2012), including industrial and domestic solid waste from landfills, sewage related debris, litter from visitors to beaches, or those originating from the unauthorized dumping of large items and trash. Lightweight solid waste items such as plastic bags are especially prominent as they are easily blown into the sea by wind. Solid waste also enters the ocean through creeks, rivers, storm drains and sewers.

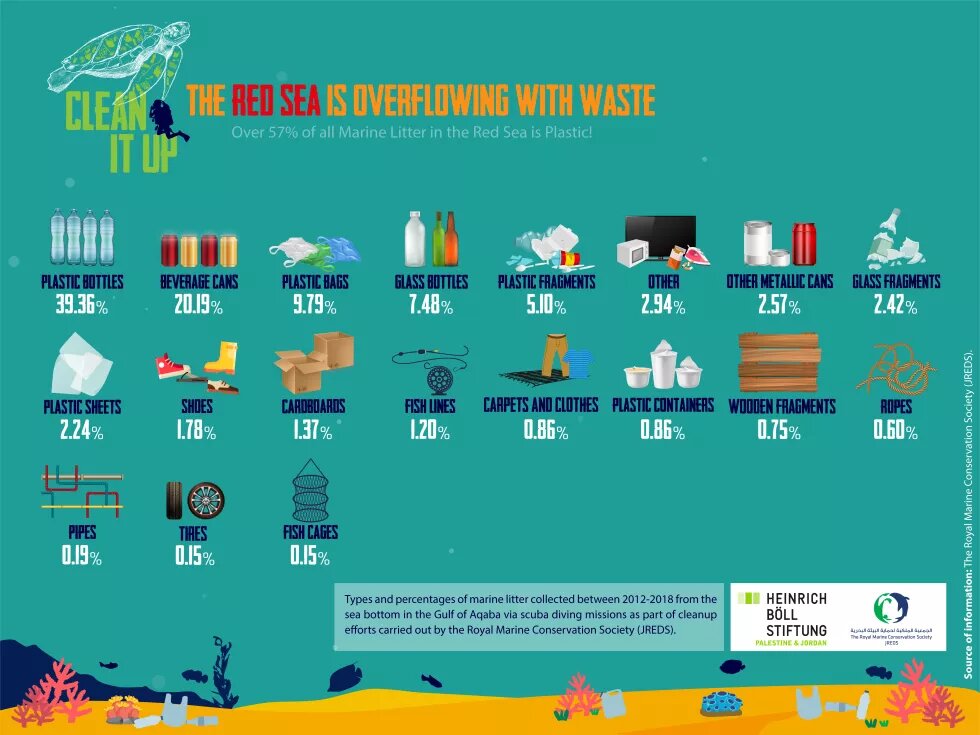

Plastic as a material for products of daily use is lightweight, flexible and durable, and can be put in a multitude of forms and shapes, making it one of the most widely used materials worldwide. Global production of plastic increased by 223-fold, from 1.5 tons in 1950 to over 335 million tons in 2016 (Plastics Europe, 2017). Consequently, rising human population combined with unrestricted production and use of plastic have led to rising amounts of plastic litter found in the world’s oceans, contributing to 60 - 80% of the marine litter on a global scale (Derraik, 2002). In the Gulf of Aqaba, scuba diving clean-up efforts by the Royal Marine Conservation Society (JREDS) showed that over 57% of all marine litter in Red Sea is plastic.

The three main types of plastic debris normally found are: macro-litter like plastic bags, meso-litter like bottle caps and micro-litter like plastic pellets originally designed for industrial use and plastic fragments from degraded plastic objects (Derraik, 2002; Eriksen, 2010). In Aqaba, plastic pellets found on the beaches are mainly connected to spills from the cargo port and are most abundant on beaches with North-South orientation due to the prevailing winds and currents (Abu-Hilal,2009).

As littering continues, studies have identified the presence of plastic fragments all around the world in the water, sediments, and even in the guts, respiratory structures and tissues of marine species (Alshawafi et al., 2018; Wright and Kelly, 2017; Derraik, 2002; Gordon, 2011).

Some of the areas that are suffering from the highest waste concentrations are those in close proximity to docks or in areas that are difficult to access for waste collection. In Aqaba, heavy metal cans are especially noticeable near coral reefs because they settle at the sea floor and are in many cases very difficult to reach.

Major Effects of Marine Litter in the Red Sea

The marine environment and marine life in the Red Sea suffer from the negative effects of marine litter. As marine litter is diverse, it has different consequences and outcomes. Plastic for example degrades into smaller particles, which can be swallowed by animals and enter the food chain – which can eventually even end up on a person’s plate. Moreover, some plastics degrade into Bisphenol A (BPA), which some researchers claim has a chemical structure like the hormone estrogen and thus can interfere with the hormone system. In a recent study it was found to affect the nervous system and cause malformed cells in embryos of marine invertebrates.

Marine debris becomes visible to most of us only once it is washed ashore. This ruins the experience of beach visitors, as it is not a pleasant view. The damage from marine debris across the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) region for fishing, shipping and tourism industries has been estimated to be up to $1.265 billion annually (APEC Marine Resources Conservation Working Group, 2009).

Fishing can create environmental problems in the marine environment. It largely depends on the type of fishing gear, the nature of the area, the targeted type of fish, and the skills and ethics of the fisherman. Aside from the direct consequence of fishing in reducing fish stock, it affects marine species through the waste produced by damaged or lost fishing gear, especially when it is made out of plastic. Fishing lines and nets belong to the most harmful plastic wastes to corals as they get entangled in them and can be especially damaging once humans attempt to pull them out. The abandoned fishing gear may also act as traps to many marine species, leading to entanglement of marine life causing injury, starvation, suffocation and death. This phenomenon of unintended continued catching of fish is called “ghost fishing” (Ghost Fishing, n.d.). Moreover, as the fishing nets that are used for commercial fishing are made out of synthetic fiber, they will degrade very slowly.

When plastic waste is released into the sea, it can be swallowed by marine animals that mistake it for food. A famous example is the sea turtle that confuses a white plastic bag for a jellyfish because they look the same. Animals may also consume the plastic when it is attached to their natural food, which causes a loss of nutrition, injury to the animal’s intestines and can even lead to death.

The impact of marine litter, through entanglement and ingestion, on threatened species of the region in particular is largely unexplored. However, one of the main issues for marine mammals is accidental drowning (PERSGA, 2006) that is believed to be attributed to ghost fishing.

Taking Action against Marine Litter – The Example of JREDS

A first step to alleviate the situation with marine litter is to enhance the awareness of people and to change their behavior. Also, stricter laws for the protection of the environment are needed as well as sufficient enforcement and implementation of these laws. Furthermore, adequate disposal facilities, recycling regimes and less consumption of plastic, especially in the packaging sector, can all help reduce the amount of litter reaching the sea. Only with a decrease in marine litter and impactful ecological management, can the conservation of the unique habitat of the Red Sea be realized.

The Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan (JREDS), an hbs partner, is working towards that end in the Gulf of Aqaba and is committed to preserving and protecting the local marine environment.

JREDS activists take part in the annual “Clean up the World Campaign”, an international program held under the patronage of United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), in which 35 million volunteers participate worldwide to clean up their environment. JREDS organizes the activities of this campaign in Aqaba, Jordan. The events are typically carried out in cooperation with several stakeholders such as governmental authorities (Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority and the Governorate of Aqaba), private sector institutions, NGOs and civil society organizations, schools, as well as thousands of volunteers. Several activities are carried out to create and enhance awareness about marine litter in the Gulf of Aqaba. These activities include educational programs, beach and ocean clean-ups, competitions for creative recycling methods, and workshops on waste-minimization. In 2014, JREDS organized an art show in Amman titled "The Sea...the Final Destination". Accumulated from several “Clean-up the World” Campaigns, a total of five tons of collected waste was displayed in the capital Amman, in the form of artistic pieces, for pupils and the general public to witness the huge amounts of waste that can be collected in such a short stretch of beaches.

The result of the yearly clean-up campaigns is the reduction of marine litter on the shores of the Gulf of Aqaba. However, despite all these efforts, the struggle against the harmful effects of litter on the marine environment, human health, and the economy is still ongoing.

Furthermore, JREDS has been working with scuba divers who collected over 8,000 kilograms of marine litter between 2006-2018 from the sea bottom in the Gulf of Aqaba. Moreover, in a regional project which was carried out in cooperation with Jordan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Sudan and Djibouti, JREDS worked on a study about the distribution and effect of waste in the Red Sea an on its shores. The one-year project included 15 clean-up campaigns in five popular diving sites, resulting in the collection of 603 kilograms of waste on land and 487kg of waste underwater.

Another part of JREDS is the Sustainable Development Program in which the following three policies initiated by the Foundation of Environmental Education (FEE) are implemented. Firstly, the Blue Flag program that consists of a voluntary eco-label for beaches which ensures high quality of water, safety and health. Secondly, the Green Key program which also is an eco-label, aimed at tourism facilities to increase their sustainability and foster responsibility towards the environment. Lastly, the Eco-Schools which is a worldwide educational program on the environment and sustainability. In these programs JREDS works with seven beaches, 30 hotels and more than 108 schools in Jordan to realize the best environmental practices and thus to safeguard the marine ecosystem.

For the past two years, JREDS and the Heinrich Böll Foundation/ Palestine & Jordan collaborated on the organization of workshops in Aqaba with local environmental activists and organizations. This year's workshop included debates on topics such as the effects of marine litter on the Red Sea, possible management schemes in light of national strategies, civic activism and local community initiatives. It also included a visit to environmentally-friendly institutions working in Aqaba, a marine tour to see the unique coral reefs and marine life of the Red Sea as well as the impact of marine litter on it. Moreover, participants of the workshop took matters into their own hands when they conducted a clean-up on one of Aqaba’s highly polluted beaches, pulling out dozens of bags full of plastic marine litter washed ashore in just a short period.

However, the continuing problem of marine litter remains. In order to change, it will not only need the necessary infrastructure, such as recycling regimes and stations, sustainable disposal facilities and efficient supply chains, but also an increase in awareness, more consumer and producer responsibility and the implementation of economic incentives, such as fees and taxes, enforcing environmental protection laws and removing existing marine litter from the sea and its shores.

References:

BIBLIOGRAPHY Allsopp, Michelle, Adam Walters, David Santillo, and Paul Johnston. 2006. Plastic Debris in the World's Oceans. Greenpeace.

Alshawafi, A., M. Analla, E. Alwashali, M. Ahechti, and M. Aksissou. 2018. "Impacts of Marine Waste, Ingestion of Microplastic in the Fish, Impact on Fishing Yield." International Journal of Marine Biology and Research 2475-4706.

Arrigoni, Roberto, Michael L. Berumen, Danwei Huang, Tullia I. Terraneo, and Francesca Benzoni. 2017. "Cyphastrea (Cnidaria : Scleractinia : Merulinidae) in the Red Sea: phylogeny and a new reef coral species." Invertebrate Systematics (31): 141-156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1071/IS16035.

Blepp, M., and G. Mehlhart. 2012. "Study on Land – Sources litter (LSL) in the Marine Environment, Review of Sources and Literature." Technical Report.

Depledge, M.H., F. Galgani, C. Panti, I. Caliani, S. Casini, and M.C. Fossi. 2013. "Plastic litter in the sea." Marine Environmental Research 92: 279-281. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2013.10.002.

Derraik, José G.B. 2002. "The pollution of the marine environment by plastic debris: a review." Marine Pollution Bulletin 44 (9): 842-852. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-326X(02)00220-5.

DiBattista, J. D., J. H. Choat, M. R. Gaither, J. P. Hobbs, D. F. Lozano-Cortés, R. Myers, G. Paulay, et al. 2016. "On the origin of endemic species in the Red Sea." Journal of Biogeography (43): 13–30. doi:doi:10.1111/jbi.12631.

DiBattista, J., M. Roberts, J. Bouwmeester, B. Bowen, D. Coker, D. Lozano-Cort, J. Choat, et al. 2016. "A review of contemporary patterns of endemism for shallow water reef fauna in the Red Sea." Journal of Biogeography (43): 423–439.

Eriksen, Marcus, Gwendolyn L. Lattin, B. Monteleone, A. Cummins, and E. Penn. 2010. "Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Plastic Pollution in the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre."

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2009. Ghost nets hurting marine environment. Accessed 12 13, 2018. http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/19353/icode/.

Ghost Fishing . n.d. Ghost Fishing » The Problem. Accessed 10 25, 2018. https://www.ghostfishing.org/the-problem.

Gordon, Miriam. 2011. "Marine Plastic Pollution: Sources, Impacts, Magnitude of the Problem." Presentation held on the Plastic Pollution Prevention Summit.

JREDS. 2016. "Clean Up the World." Unpublished Report, 52.

JREDS. 2017. "Clean Up the World." Unpublished Report, 52.

JREDS. 2014. "Final report on DROSOS research activities." Unpublished, 18.

Kelly, Frank J., and Stephanie L. Wright. 2017. "Plastic and Human Health: A Micro Issue?" Environmental Science & Technology 51 (12): 6634-6647. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b00423.

Khalaf, M., and A. Disi. 1997. Fishes of the Gulf of Aqaba. National Library.

McIlgorm, A., H. F. Campbell, and Rule M. J. 2008. Understanding the economic benefits and costs of controlling marine debris in the APEC region (MRC 02/2007). A report to the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Marine Resource Conservation Working Group by the National Marine Science Centre. University of New England and Southern Cross University, Coffs Harbour, NSW, Australia: National Marine Science Centre.

Messinetti, S., S. Mercurio, and R. Pennati. 2018. "Bisphenol A affects neural development of the ascidian Ciona robusta." J Exp Zool A Ecol Integr Physiol. doi:10.1002/jez.2230.

OR&R's Marine Debris Division. 2018. Marine Debris Program - Impacts. 12 12. Accessed 12 13, 2018. https://marinedebris.noaa.gov/discover-issue/impacts.

PERSGA. 2006. State of the Marine Environment, Report for the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden.

PERSGA. 2006. State of the Marine Environment, Report for the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. Jeddah: PERSGA.

PERSGA. 2002. Status of the Living Marine Resources in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden and Their Managemen. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

—. 2002. Status of the Living Marine Resources in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden and their Management.

PERSGA/UNEP. 2008. Marine Litter in the PERSGA Region. Jeddah: PERSGA.

PlasticsEurope. 2017. "Plastics - the Facts 2017. An analysis of European plastics production, demand and waste data." PlasticsEurope - Association of Plastics Manufacturers.

Santos, Isaac, Ana Cláudia Friedrich, Monica Wallner-Kersanach, and Gilberto Fillmann. 2005. "Influence of socio-economic characteristics of beach users on litter generation." Ocean & Coastal Management (48): 742-752. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2005.08.006.

The Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel (STAP). 2011. "Marine Debris: Defining a Global Environmental Challenge. A STAP Advisory Document." Global Environment Facility Council Meeting.

Veiga, J.M., Fleet, D., Kinsey, S., Nilsson, P., Vlachogianni, T., Werner, S., Galgani, F., Thompson, R.C., Dagevos, J., Gago, J., Sobral, P. and Cronin, R. 2016. "Identifying Sources of Marine Litter. MSFD GES TG Marine Litter Thematic Report." JRC Technical Report. doi:10.2788/018068.